Events Calendar

Current Weather

Algonquin Park Archives Blog

|

|||

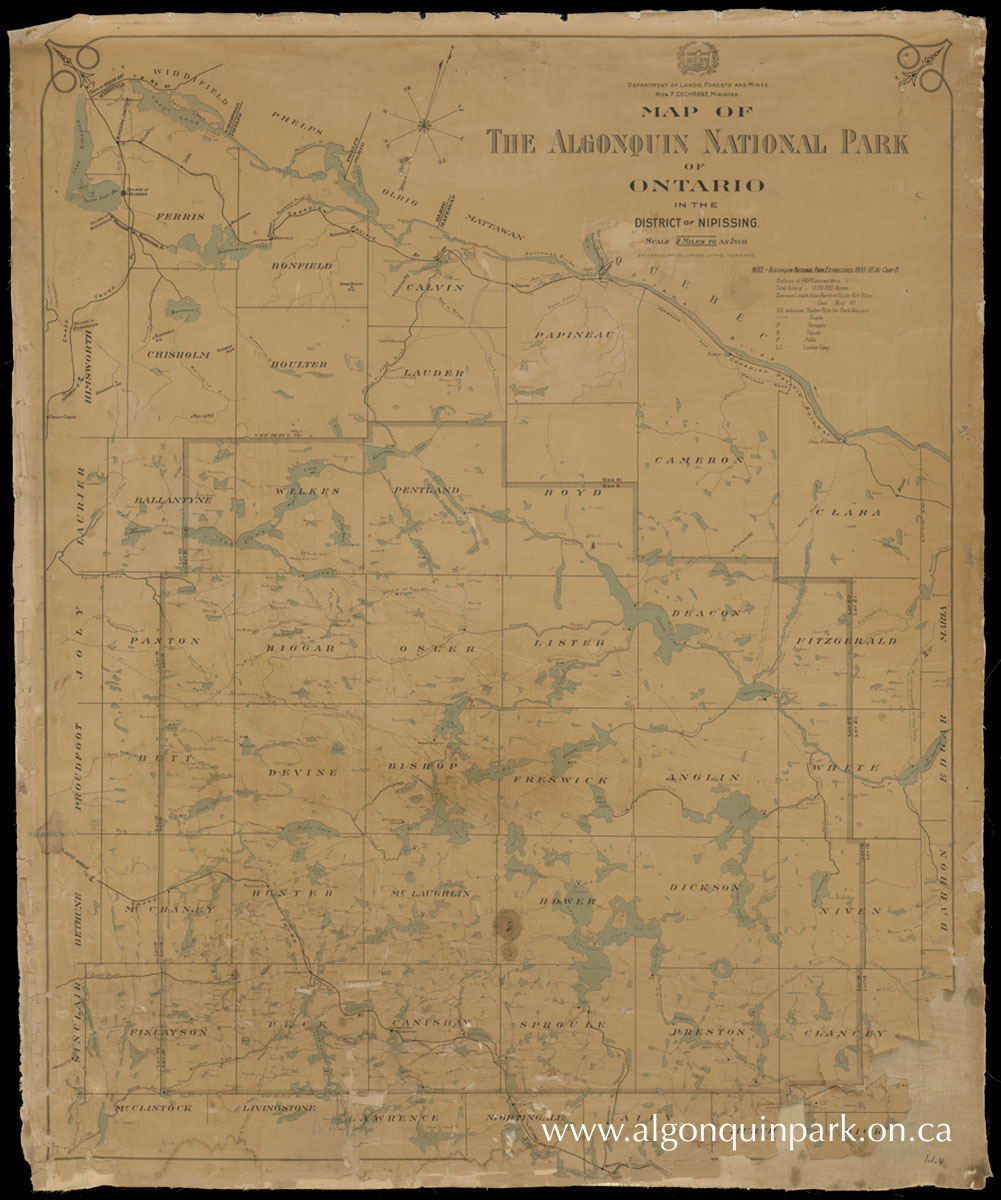

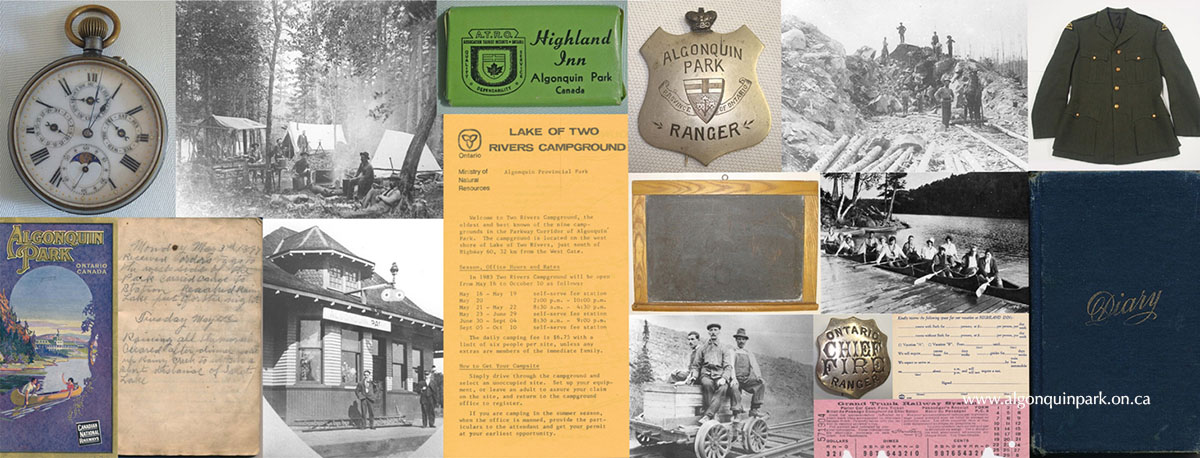

The Algonquin Provincial Park Archives and Collections (APPAC or “Archives”) is the repository for artifacts of significance to the natural and cultural history of Algonquin Park and is owned by Government of Ontario, with substantial funding and operating assistance from The Friends of Algonquin Park, a registered Canadian charity.

The Archives is dedicated to the education, interpretation, and conservation of Algonquin Park’s heritage. Their mandate seeks to promote knowledge & awareness, spark curiosity, and inspire visitors to develop a deeper connection with the natural and cultural history that surrounds them.

More blogs posts are coming in the weeks ahead, check back again, or follow our social media for updates.

December 23, 2025

Seasons Greetings

Dashing through the snow

In a one-horse open sleigh

O'er the fields we go

Laughing all the way

Bells on bobtails ring

Making spirits bright

What fun it is to ride and sing

A sleighing song tonight

Image: A sleighing party outside Canoe Lake Station, Christmas Day, 1913. Local residents and visitors from nearby communities have gathered to celebrate the holiday. APPAC, 1972.3.29, Thomas & Wilkinson Collection.

With the fresh snowfalls coating Algonquin Park’s trees, anticipation grows for quickly approaching festivities. Same holds true for the people who once called Algonquin Park their home. For them, Christmas was yet another time to enjoy the company of their tight-knit communities. Above we see a sleighing party gathered together at Canoe Lake Station. Members of the Thomas, Wilkinson, Worsley, and Benoit families of Canoe Lake, Joe Lake, and Kearney, ON were transported by J.S. “Shan” Fraser to Mowat Lodge for a sleigh ride and get-together. The image was captured Christmas Day, 1913.

Holiday traditions have long histories, and as such we often see them represented in the Algonquin Provincial Park Archives and Collections (APPAC; “Archives”). Many of us will remember the nervous feeling of performing a piece for the school concert. School children in Algonquin Park also performed Christmas concerts for their families, singing carols and reciting poetry. These concerts would take place at the small one-room schoolhouses, or other community gathering places. In her book “Joe Lake: Reminiscences of an Algonquin Park Ranger’s Daughter”, H. Eleanor (Mooney) Wright describes the Christmas concert as “the event of the season” at Joe Lake. Held in the wonderfully decorated rotunda of the Hotel Algonquin, participants sang carols, children recited poems, and adults put on a play.

|

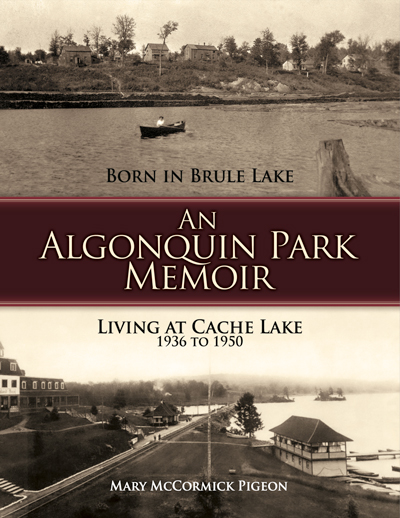

An Algonquin Park Memoir by Mary McCormick Pigeon |

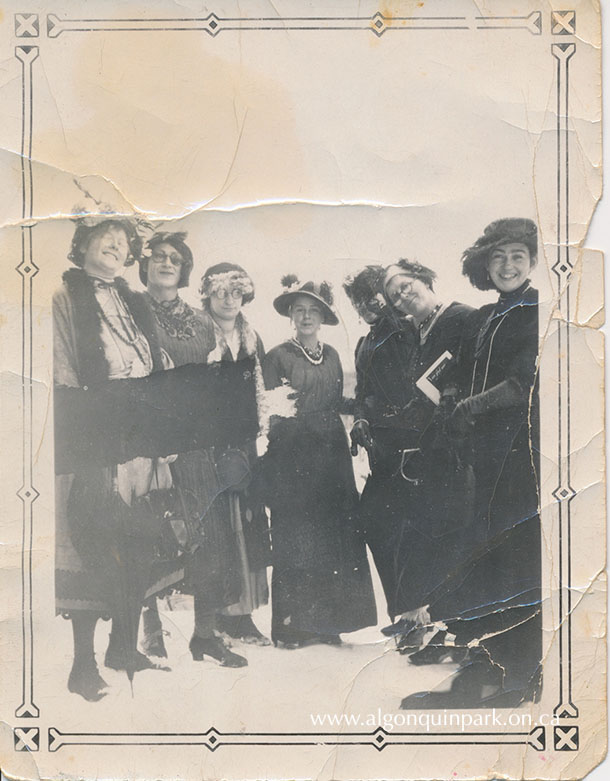

Image: Cast members of "The Booneysville Uplift Society”, performed at the Christmas concert at the Hotel Algonquin, c. 1931-1932. Left to right: Ethel Mooney, Omer Stringer, Mrs. Budarick, Mabel Stringer, Molly Colson, Lila Stringer, Mary (Colson) Clare. APPAC, 1986.2.1, Mary Colson Clare.

Many traditions centre around food, whether it be traditional dishes, favourite baked goods, or seasonal sweets. Wright describes the sweet treats served after the play at Joe Lake. Santa would arrive with popcorn balls, homemade fudge, candied apples, and gifts for all the children. Refreshments were served for all who attended. In “An Algonquin Park Memoir”, Mary McCormick Pigeon recounts that in 1946 her schoolchildren and their parents were invited by the Department of Lands and Forests to a party at the staff house on Cache Lake where lunch was served.

Image: Holiday feasts were prepared throughout the small communities in Algonquin Park. This 1926 picture of Mary McCormick as a young girl living with her family at Brule illustrates the centrepiece to most traditional holiday meals. APPAC, 2022.12.103, McCormick and Pigeon Family.

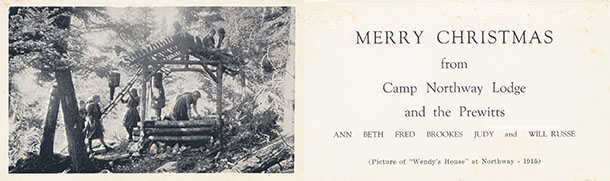

With today’s technological advances, friends and family can send holiday messages by e-mail or messenger apps, but many still enjoy the thrill of receiving traditional cards. Cards can also be promotional items, reminding recipients of a business or person. In the Archives, one example comes from the history of the Park’s longest running youth camp, Camp Northway Lodge. First opened in Algonquin Park in 1908, the camp still welcomes girls today. Like many camps, Camp Northway communicated with campers, parents, and alumni during the off season. Their Christmas cards featured historical photographs from the camp’s past and artwork from their biography publication. Beyond representing interesting examples of marketing, the cards help researchers trace changes in ownership, history of the camp, and alumni events.

Image: Camp Northway Lodge Christmas card, c. 1950s – 1970s featuring a 1915 historical image from the camp. APPAC, 2016.18.171.1, Pollee Menoher Phipps Collection.

Inside and outside the home, decorations represent a key tradition for many families. Rose Thomas and Jack Wilkinson are well known in the Archives for their photography collection, capturing hundreds of images while living in Algonquin Park and working alongside (and after) Rose’s parents, Edwin and Emily. The collection contains a multitude of joy-filled images of the Christmas decorations and meals in their home at Kish-Kaduk Lodge on Cedar Lake. In addition to their own real Christmas tree, they decorated trees outside, often captured in images with their wild friends. Although their decorating traditions remain similar from year to year, we can tell the holiday images span many seasons by the changing position of the tree or new decorations appearing on the ceiling. But of course, the gifts underneath the tree vary from one year to the next too.

Images: Christmas memories from Kish-Kaduk Lodge, Cedar Lake, c. 1950s – 1970s. Top to bottom, left to right: Edwin Thomas, Rose Thomas, Jack Wilkinson, Emily Thomas; a raccoon under a decorated tree; Christmas decorations; Jack Wilkinson and Rose Thomas wearing festive hats at a holiday meal; a deer lying down beside a decorated tree; a cat lounges by the fireplace surrounded by Christmas decorations. APPAC, 1972.3.235.11; 1972.3.110.118; 1972.3.110.109; 1972.3.110.113; 1972.3.143; 1972.3.111.102, Thomas and Wilkinson Collection.

|

Make a charitable donation to assist us in protecting Algonquin Park's cultural heritage for future generations. |

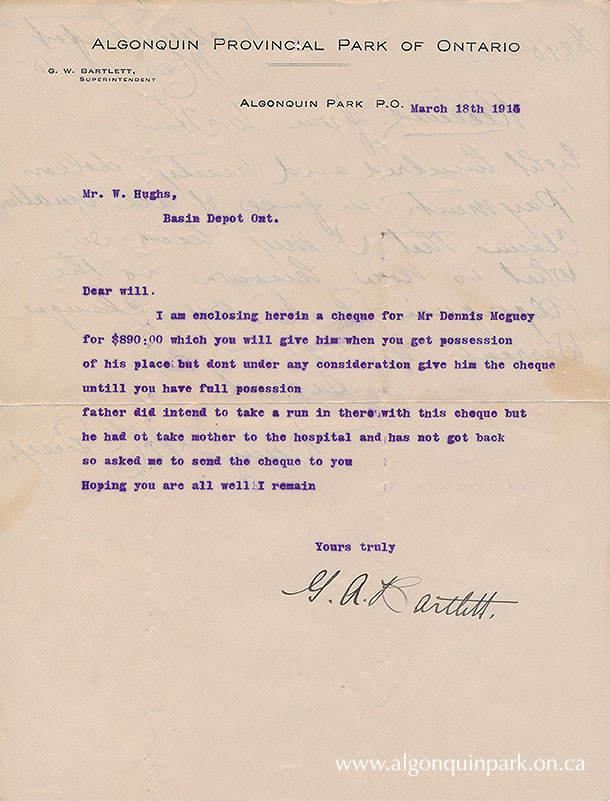

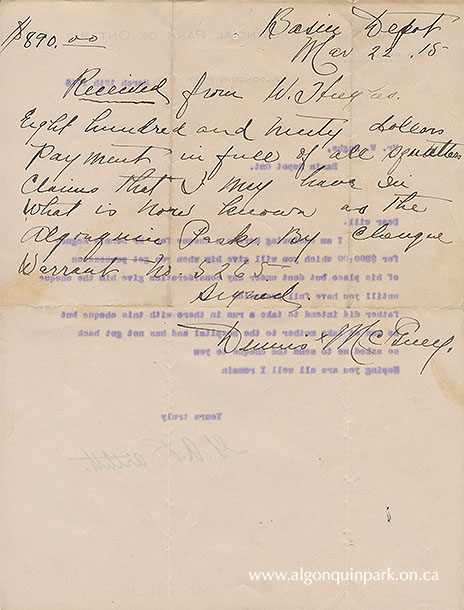

We can also trace time by the appearances of individuals as they age, or the absence of family members as they pass on. At the core of our traditions are the people we share them with and the memories we create. In Superintendent George Bartlett’s 1914 correspondence to Ranger William Hughes, he wishes Hughes and his family good health and best wishes for Christmas and the New Year. Bartlett comments that he expects he and Mrs. Bartlett will remain at Cache Lake over the holidays as “she is not well enough to go anywhere and I don’t expect any of our people can come.” (APPAC, 2020.20.10, Estate of Janet Ivel (Hughes) Gurr). Quotes like these remind us to treasure our relationships and the special memories we make during the holidays as we connect in our own unique and treasured ways.

All the best to you and yours in 2026!

Learn More

Learn more about the Algonquin Provincial Park Archives & Collections

- Explore the online database of photographs, archival records, and artifacts.

- Contact the Collections Coordinator to schedule a research appointment or discuss a donation.

- Read more by purchasing historical publications in The Friends of Algonquin Park’s bookstore.

- Support the Archives with a financial donation via The Friends of Algonquin Park, a Canadian registered charity, to assist us in preserving Algonquin Park's cultural heritage for future generations.

December 17, 2025

A Hike Down Memory Lane

On June 28, 2025, The Friends of Algonquin Park opened the newest interpretive hiking trail in Algonquin Park. Located at the Algonquin Park Visitor Centre, the Fork Lake Trail is a 2.4 kilometre loop that offers short, steep climbs from lake level to high hilltops with scenic views.

On June 28, 2025, The Friends of Algonquin Park opened the newest interpretive hiking trail in Algonquin Park. Located at the Algonquin Park Visitor Centre, the Fork Lake Trail is a 2.4 kilometre loop that offers short, steep climbs from lake level to high hilltops with scenic views.

The event motivated the Algonquin Provincial Park Archives and Collections (APPAC; “Archives”) to take a stroll (or hike) down memory lane to explore the history of the Park’s trail system. There are many types of trails in Algonquin Park, from dog sled and cross-country skiing to portages and backpacking trails, but this post will focus solely on the history of interpretive trails, namely those designed to be self-guided.

Image: Entrance to the Fork Lake Trail at the Algonquin Visitor Centre, June 2025.

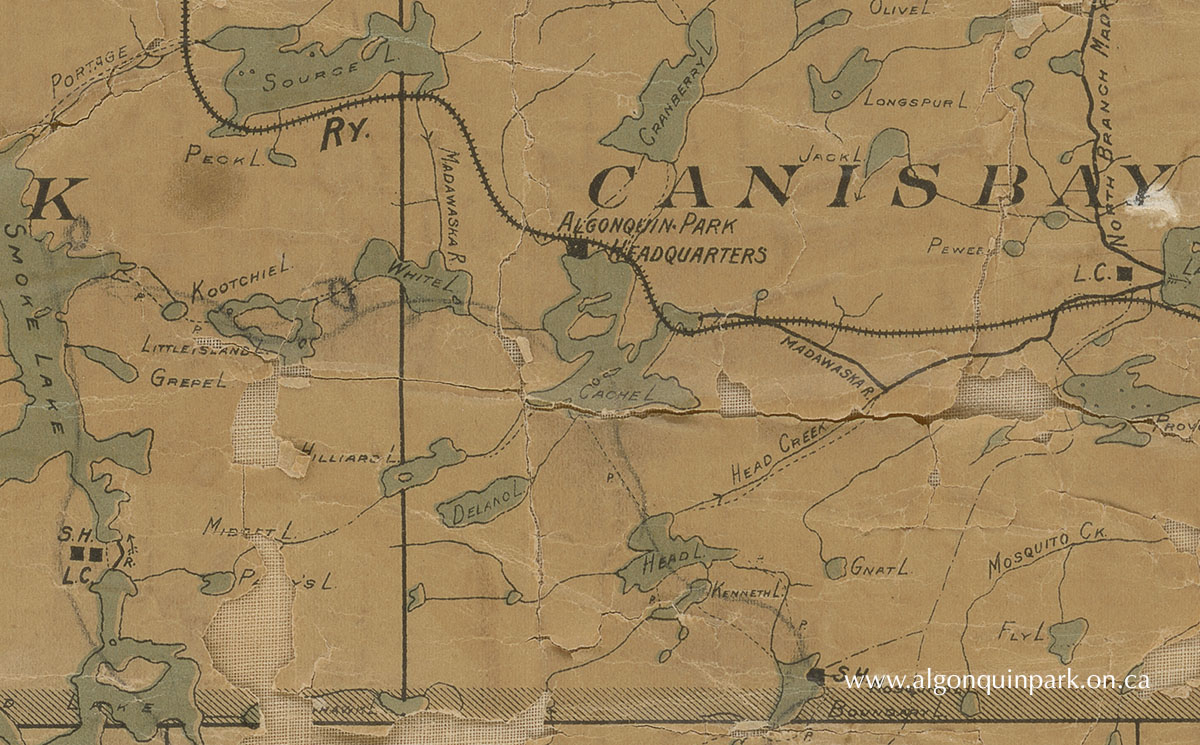

Interpretive trails were originally known as nature trails, and we can trace the very first all the way back to October 1938. This trail was the portage from Cache Lake to Canisbay Lake and was “set-out” by Park Ranger Dr. Duncan MacLulich. MacLulich was a biologist by training, and the Park Superintendent at the time, Frank MacDougall, wanted to have a dedicated biologist on staff, but the position did not exist. Instead, MacLulich was hired as a Ranger and encouraged to complete scientific studies on the side. The Archives also considers him to be the first Park Naturalist on staff through his role with the Canisbay Nature Trail.

MacLulich placed nature signs on trees along the portage. The signs were blocks of wood about six inches long, two inches high, and one inch thick (15.24x 5.08 x 2.54 cm). They had a bevelled edge and were painted yellow with black letters on them. The signs simply identified the name of the tree to those passing by. MacLulich also planned a nature trail for the Tanamakoon Trail, but the war intervened and his time in the role ended in September 1939.

When Algonquin Park’s Naturalist Programme and first museum began in the early 1940s, so too does the re-emergence of the nature trail system. In 1946, 41 new signs identifying plants and trees were added to the Canisbay Nature Trail, and the entrance to the trail was marked at the highway. A year later, 47 labels were prepared at the request of the proprietor of Whitefish Lodge, Mr. J. Connolly, who wished to brush out a trail that fall. Heavily used portages in the Park were also labelled: Smoke Lake/Canoe Lake; Burnt Island Lake/Jay Lake, and Burnt Island Lake/Little Otterslides Lake.

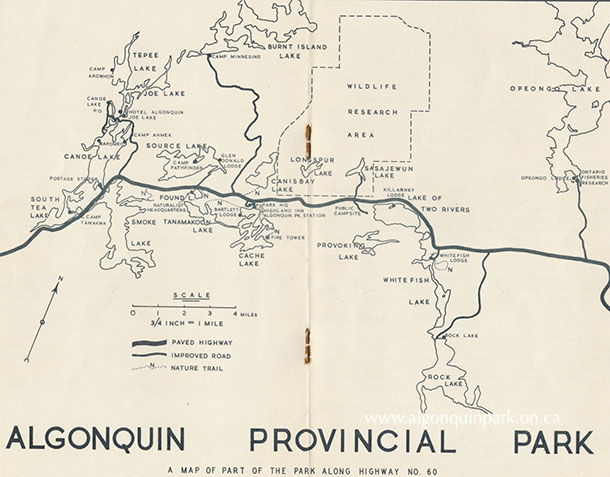

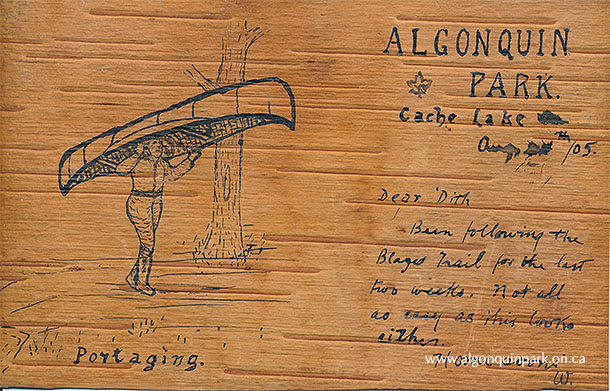

Image: Map of part of Algonquin Provincial Park along Highway 60, from the “Nature Program” booklet, c. 1949 – 1952. The booklet describes the trails to visitors: “The entrances to the nature trails are marked along the highway. Here the visitor will find the trees and plants labelled as well as other interesting items of natural history. Please do not pick or destroy the plants along the trail and do not litter the woods with lunch papers, cigarette packages, etc. … Leave the trails so that others also may enjoy them.” APPAC, 2023.23.1.

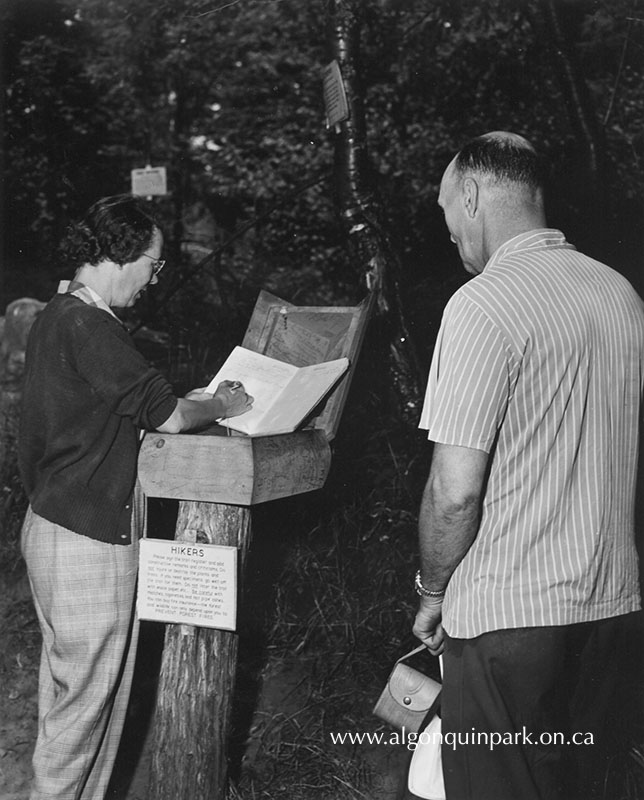

In the 1950s we see continued growth and definition of the nature trail system. Four trails are maintained, namely Deer Lake, Canisbay, Two Rivers, and Lookout. For today’s frequent Algonquin Park visitors, most of these names will be familiar except perhaps for Deer Lake. This trail began on Highway 60 at picnic grounds near Smoke Lake and travelled south to a portion of the lake known as Deer Bay. Nature Trail signs continue to identify plants, shrubs, trees, and other points of interest. Registration books were placed in boxes on each trail, and hikers were encouraged to sign the booklets. The data was helpful to Park Staff in tracking visitation numbers, although in later years they faced much trouble in people stealing the books.

Image: Hikers signing a trail register book on a nature trail, 1953. Spot the signs in the trees. APPAC, APM 874.

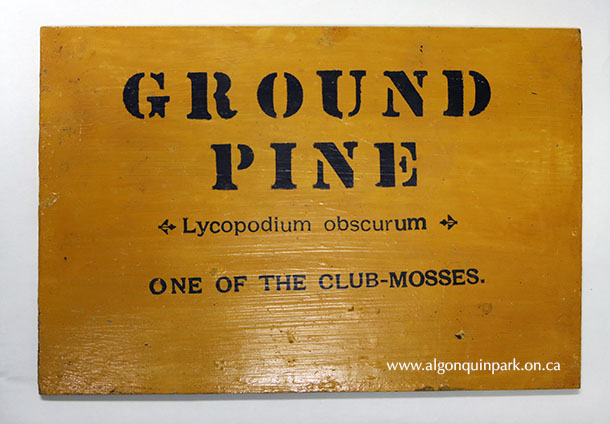

Park Naturalists experimented for many years in finding the right methodology for crafting their signs. At first 5” x 9” (12.7 x 22.86 cm) Masonite boards were used and painted on one surface with chrome yellow paint. When dried, black enamel lettering was applied. The quickest way to letter was to apply ink onto a stencil with a spray gun. Once dry, the sign was varnished, with special care taken to shellac and varnish the edges to protect against the weather. Later, a special typewriter with Royal 6 Gothic type was used to print the text on a transfer which was then slipped off, after being moistened. The text was applied to a 7” x 9” (17.78 x 22.86 cm) piece of plywood which was varnished or painted beforehand. Once applied, the label was sprayed with clear plastic.

Image: Nature trail sign for “Ground Pine”, 6” x 9”, Masonite painted yellow and stenciled with black, c. 1940s – 1950s. The sign identifies the Latin name “Lycopodium obscurum” and a short phrase “one of the club-mosses.” to hikers passing by. APPAC.

Park Naturalists weighed the pros and cons of their methods and hoped to continue to find the best sign which would hold up to the elements on the trails. In the following years they would try applying the text to thin sheets of galvanized metal, only to find that vandals could easily bend the signs in half. The best compromise was to attach the metal sign, which held up well to the weather, to a piece of plywood, which could not be easily vandalized.

Image: Ontario Department of Lands and Forests nature trail sign, 7” x 9”, metal on plywood backing, c. late 1950s – 1960s. This sign is for “Yellow Birch” and explained to visitors: “The bark is smooth and yellowish except on large trees where it breaks up into large brownish plates. The hard strong wood takes a high polish and is valuable for veneer furniture and flooring. The tree is a favourite food of deer which may be the reason for the scarcity of birch seedlings in this area.” APPAC.

The nature trail system continued to grow and fluctuate from year to year in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1956, Deer Lake Trail was closed for the season, due to wetness experienced the previous year. A new trail into Pinetree Lake, on the east side of Algonquin Park, was built and finally opened on August 1, 1956. With only one staff vehicle for the Naturalist Programme, maintenance and construction were difficult due to the distance from the Park Museum, located at Found Lake, and just before Labour Day a forest fire was started by a trail-user. The year-end report explains, “Because of this fire, it has been suggested that the Nature Trails be kept in Peck and Canisbay Townships, where travel permits are not required. This restriction should not be necessary, as the fire could just as easily have been started on Canisbay Lake as any other place. Within a few years attractions will quite definitely be needed at the east end of the Park.” Pinetree Lake Nature Trail was closed, but this prediction for the east side of Algonquin Park would ring true, but after more than a “few years”.

This era of change and experimentation continues in 1958 with the opening of yet another new trail, this time leading to Jack Lake. Today’s Park visitors would know this location as the Hemlock Bluff Trail. Trail names were changed in the 1960s to better represent the features hikers could expect to visit on the trail. Jack Lake became Hemlock Bluff, Deer Lake became Hardwood Hill, and the newly constructed Hains Lookout trail became Hardwood Lookout. In 1959, Park visitors also experienced a change in the location of Lookout Trail when it switched from the north side of Highway 60 to the south to allow the north trail to recover and to give staff time to clear vandalism from the rocks.

Image: Left – Entrance to the Hemlock Bluff Nature Trail with cars parked along Highway 60, 1961. APPAC, APM 873. Right – The Hardwood Nature Trail Sign in Algonquin Park’s artifact collection. APPAC, 2024.26.1. In 1961, a new standardized style of highway signs for nature trails was launched across all Provincial Parks in Ontario. Algonquin Park Naturalist Programme’s year-end report of the year stated they were “very eye-catching, and have evoked many favourable comments”.

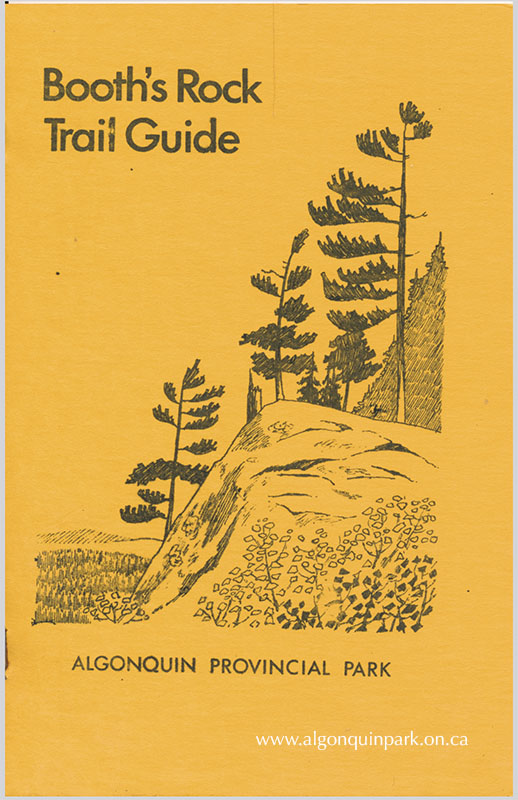

With the creation of Booth’s Rock Trail in 1967, Algonquin Park begins its trail guide tradition. The Naturalist Programme year-end report explains: “This trail starts on the old railway at the easterly end of the Baulke Campsite and describes a four mile long loop passing the Rosepond, Gordon Lake, Booth’s Rock, Barclay Estate, and returns to the starting point along the railway. The trail was brushed out and marked with yellow can lids. Numbered posts were set in the ground at points to be interpreted in the new trail guide leaflet. The final draft of the trail guide leaflet will be approved this winter and will be available for use when the trail is opened in spring of 1968”. The trail was officially announced in the June 26, 1968, "The Raven" with subsequent "The Raven" articles throughout the summer tracking the progress of the trail guide. At first, trail users would be supplied with a folder containing corresponding numbers and printed discussion of interesting trail features. In July, the first edition of the trail guide was released, but naturalist staff made sure to explain it was rushed production and welcomed suggestions from trail users. This system of carrying a booklet around the trail must have seemed quite strange to hikers familiar with the signs they would normally encounter.

Image: Cover of Algonquin Park’s first trail guide, created in 1968 for the newly constructed Booth’s Rock Trail. APPAC, M-7-2b.

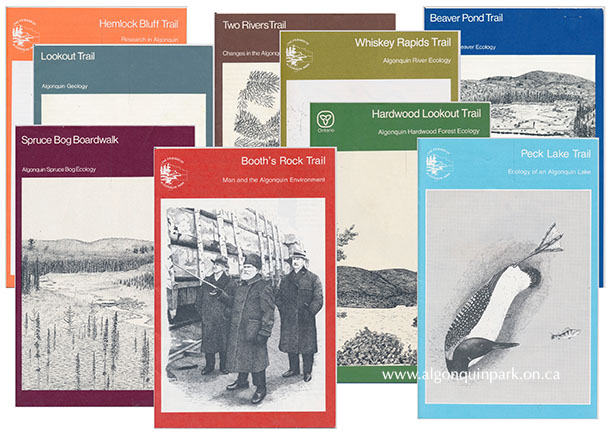

The trail guides allowed staff to provide much more interpretive content than the old system of signs and provided the key to the new trail system which emerged in the 1970s. Each trail would have a dedicated trail guide and explore a specific habitat or topic to create a systematic and thematic exploration of the Algonquin environment. With the need for only one deciduous forest trail, Hardwood Hill (formerly Deer Lake) was closed, with a new trail laid out at Hardwood Lookout overlooking Smoke Lake. Four trails are added to the existing system, namely Spruce Bog Boardwalk, Beaver Pond, Peck Lake, and Whiskey Rapids, to create “the nine” interpretive trails. One exception is the Barron Canyon trail which first appears in reports in 1972. Located outside of the Highway 60 corridor, it is not considered part of the “nine”. At first it has a small Gestenered trail leaflet but does receive its dedicated trail guide in the new system until 1987.

In 1972, a combination trailhead sign and trail guide dispenser was designed and seven were being constructed over the winter. They would be put into operation as the various trail guides became available. Trail users could use the guide and return it when they were done, for free, or buy the guide for 10 cents. The following year, the first trail guide dispensers were used at Beaver Pond, Lookout, and Hardwood Lookout Trails. The honour system resulted in a small absolute loss of $135.96 or less than 0.25% per registered trail user (60,000 trail users), and the system was considered a success.

Image: By 1976, “the nine” trails of the new interpretive system have dedicated trail guides available to users at special trailhead dispensing signs. Text by Dan Strickland and illustrations by Howard Coneybeare. APPAC, M-7-1a; 1g; 1p; 2d; 2h; 2m; 3b; 3m; 3v.

In the 1980s, the trail system once again began to grow. Mizzy Lake (1982-83); Brent Crater (1987); Track and Tower (1989-90); Bat Lake (1989-90); Berm Lake (1992-93); Algonquin Logging Museum (1992); Centennial Ridges (1993) and Big Pines (2001) rounded out the system trail users enjoyed.

Twenty-four years later, the latest in the series of interpretive walking trails, the Fork Lake Trail was opened to the public on June 28, 2025. As a celebration of Algonquin’s habitats, its path takes hikers to spruce bogs, lakes & rivers, deciduous forests, coniferous forests, and beaver ponds. The trail guide (forthcoming!) encourages visitors to explore the many trails in Algonquin Park and will soon join the collections on bookshelves of dedicated Park hikers worldwide. Like many other trails built since The Friends of Algonquin Park’s establishment in 1983, this trail is a gift from The Friends on behalf of its generous donors and in collaboration with many partners. Stepping foot on this trail and the many others across Algonquin Park lets you join a long history of hikers who have learned from and enjoyed the interpretive trail system.

Image: Camp Northway campers at the top of Skymount overlooking Cache Lake, 1918. Early visitors to Cache Lake would climb the hill from the shore of Cache Lake to the rocky outcrop where the fire tower once stood. Later, one could follow the route along the railroad tracks from Algonquin Park Station. Today, Algonquin Park visitors reach the same lookout but by a different route, that of the Track and Tower Trail. APPAC, 2001.7.37.

Learn More

Learn more about the Algonquin Provincial Park Archives & Collections

- Explore the online database of photographs, archival records, and artifacts.

- Contact the Collections Coordinator to schedule a research appointment or discuss a donation.

- Read more by purchasing historical publications in The Friends of Algonquin Park’s bookstore.

- Support the Archives with a financial donation via The Friends of Algonquin Park, a Canadian registered charity, to assist us in preserving Algonquin Park's cultural heritage for future generations.

December 8, 2025

Algonquin Park Legacy: J.R. Booth

One hundred years ago, on December 8, 1925, John Rudolphus Booth passed away at the age of 98 years old in his home in Ottawa, Ontario. He was one of the richest and most influential men in Canada, but at his request, he was buried in a humble ceremony, without an elaborate church service or even funeral music. Despite this, thousands visited Booth’s casket to pay their respects during visitation at his home. Although the family requested no flowers be brought to the simple service, the room was filled with them. Hundreds gathered on the streets to observe his casket being placed in the hearse and walked with him on the journey to his final resting place.

One hundred years ago, on December 8, 1925, John Rudolphus Booth passed away at the age of 98 years old in his home in Ottawa, Ontario. He was one of the richest and most influential men in Canada, but at his request, he was buried in a humble ceremony, without an elaborate church service or even funeral music. Despite this, thousands visited Booth’s casket to pay their respects during visitation at his home. Although the family requested no flowers be brought to the simple service, the room was filled with them. Hundreds gathered on the streets to observe his casket being placed in the hearse and walked with him on the journey to his final resting place.

Image: Portrait of John Rudolphus (J.R.) Booth, 1904. William James Topley, Library and Archives Canada, PA-012219.

Who was J.R. Booth? How did he have such an immense impact on those around him? Why is his life jointly tied with the history of Algonquin Park?

On the anniversary of his death, the Algonquin Provincial Park Archives and Collections(APPAC; “Archives”) will look at his influence on the Park, and how a simple carpenter became one of Canada’s most famous lumber magnates.

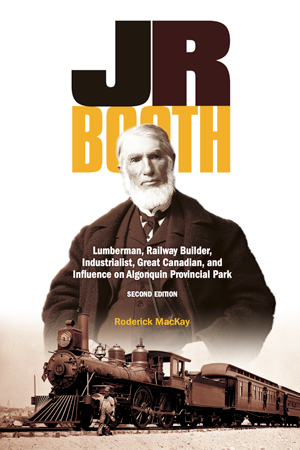

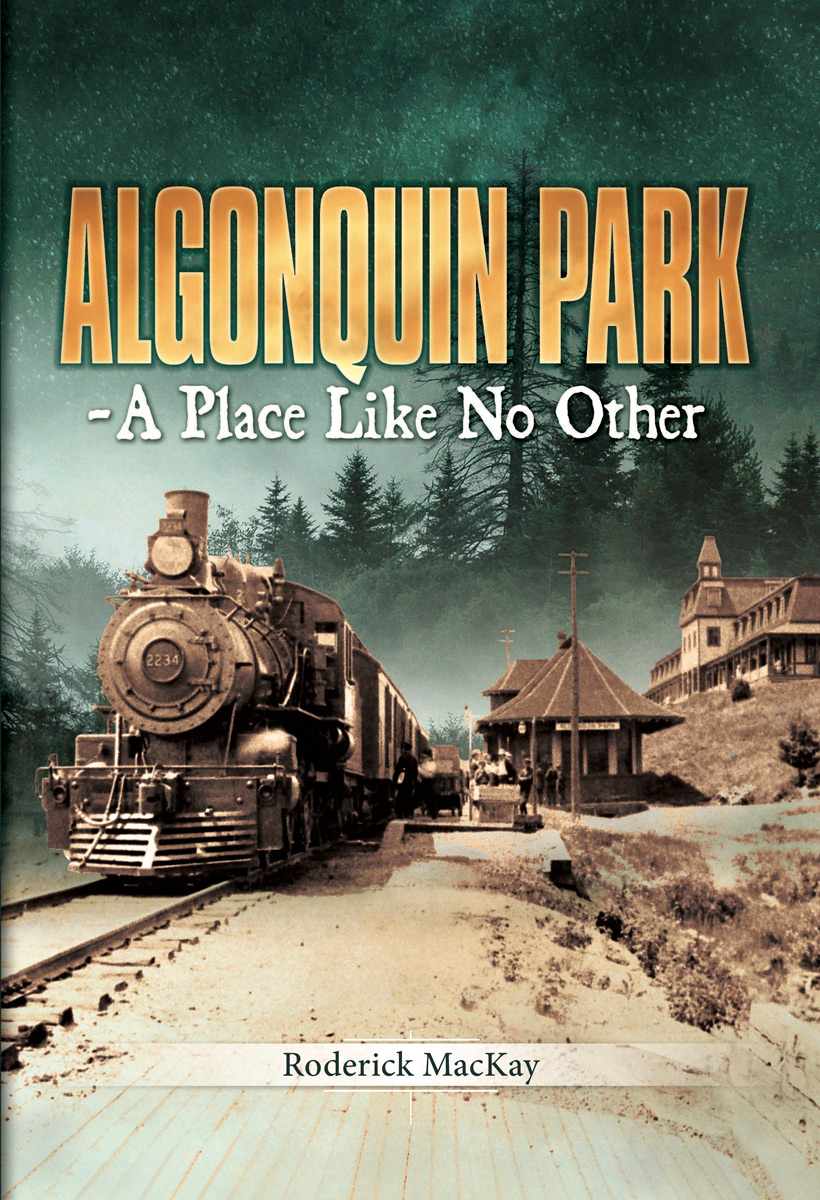

This article relies heavily on the research and work of author Rory MacKay who has recently released a second edition of his book, “J.R. Booth: Lumberman, Railway Builder, Industrialist, Great Canadian, and Influence of Algonquin Provincial Park”. To learn more about the life, personality, and impact of this Canadian on those around him, explore a copy of this beautiful book!

Image: Keen eyed observers travelling through Algonquin Park’s backcountry may discover remnants of the influences of J.R. Booth. This pile of logs, abandoned for unknown reasons in Paxton Township, bears one of the many registered timber marks for the J.R. Booth Lumber Company. But who was J.R. Booth? APPAC, x2025.26.1-4.

Born near Waterloo, Quebec, on April 5, 1827, J.R. Booth was raised with a simple upbringing, not unlike most farm children of Upper and Lower Canada at the time. His earliest work experiences took him away from the family farm, exploring the United States of America as a carpenter’s helper in New York State, joining the gold rush in California, and building railway bridges for the Central Vermont Railroad. Disappointed at his lack of progress in building his fortune, Booth returned to Canada, marrying Rosalinda Cook a short time later, on January 7, 1853. With the added pressure of starting a family, Booth continued to dream of growing his reputation and pushing himself to accomplish the most he could in life.

Image: Portrait of J.R. Booth and wife Rosalinda (Cook) Booth with their children: Ellen, Lila, Charles, and John. September 1871. William James Topley, Library and Archives Canada, PA-033271.

|

Booth, his wife, and new daughter would move to Ottawa, Ontario. As the story goes, Booth only had nine dollars in his pocket. Although equivalent to much more in today’s currency, this was still only a small amount in the early 1850s. Booth began slowly, employed as a carpenter building sawmills. In the evening, he and his wife would split roof shingles, by hand, to supplement his income. After working as manager of a sawmill, Booth operated his own machine shop and then a shingle-making factory before securing a ten-year lease on a sawmill on the Chaudière Falls.

His first big break came in 1859 when he secured the bid to supply lumber for the construction of the Parliament buildings in Ottawa. Although the original Parliament buildings burned in the great fire of 1916, a portion of J.R. Booth’s lumber is still present in the Parliamentary Library, which was saved by quick thinking staff who closed the iron doors. With his recent successes, Booth was able to purchase the sawmill he had been previously leasing. He bought a neighbouring mill and proceeded to build another. It was clear that Booth would require an even larger supply of wood for his sawmill operations.

Image: Man leaning against a stump in front of several buildings at the J.R. Booth Lumber camp at the north end of Shirley Lake, Algonquin Park, 1925. APPAC, 1976.74.3, Max Borutski.

Booth bid on and secured numerous timber limits across the Ottawa Valley and Algonquin Park, perhaps none more important than the Egan Estate timber limit on the Madawaska River. The financial gamble, called fool-hardy by many fellow lumbermen, paid off when the limits provided 150,000 to 300,000 sawlogs each season, from 1867 to 1906.

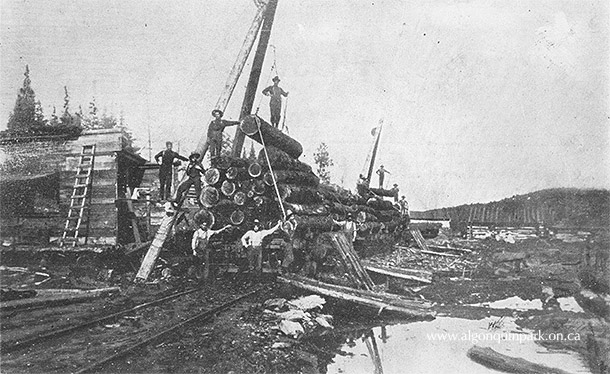

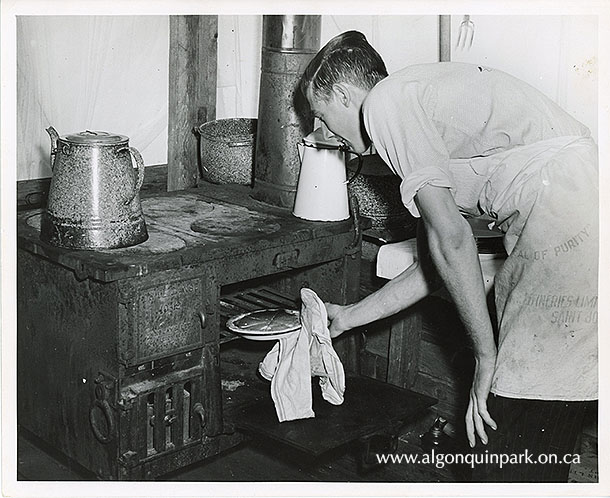

Like the numerous logging companies across Algonquin Park and Ontario, Booth hired lumbermen to work in the logging camps on his timber limits. Perhaps the main difference is that with the size of his lumber empire, Booth as an employer impacted a far greater number of lives. Each fall, thousands of men of all ages would leave their families and travel into the forests to cut, prep, and pile logs for J.R. Booth. Many came from farming families who needed the winter income to supplement their meager crops in the summer season. The men would earn $1 a day, with room and board included for their stay in the camps. The result of their work would be thousands of logs piled high along the frozen banks of lakes and rivers, awaiting the spring breakup when select crews of men would stay on to complete the river drive to Booth’s Ottawa sawmills.

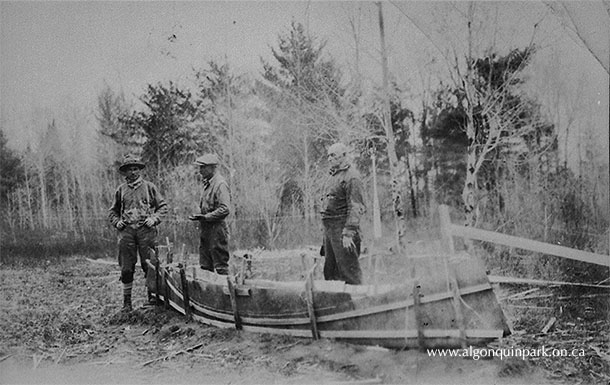

Image: Men working with a log jam on a J.R. Booth river drive. The image is thought to have been captured before 1900 on the Madawaska River. APPAC, 2023.13.1, From the Collection of Barry Donald Pretty.

|

Make a charitable donation to assist us in protecting Algonquin Park's cultural heritage for future generations. |

Always looking to expand and grow his operations, Booth was restricted by the seasonal hindrances. The only way to transport logs from his timber limits to his mills in Ottawa, and likewise lumber from his mills to the markets, was by the waterways. But, in this northern climate, water is only an ideal transportation method when it is open. The seasonal freeze-up severely hindered his business plan. If only there was a way to transport wood 365 days of the year.

The 19th century was a time of great excitement and popularity for railroad operations, and it is no surprise that an entrepreneur such as Booth would miss such an opportunity for expansion. Alongside business partner and fellow lumbermen, William G. Perley, Booth would invest and build the Canadian Atlantic Railway, connecting Ottawa to the Central Vermont Railway and the seaports of the Eastern Seaboard. But why stop there?

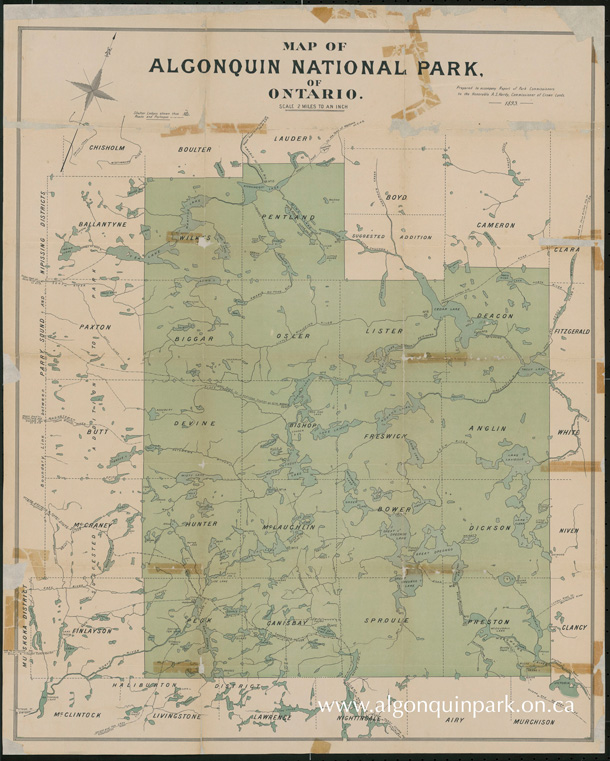

As early as 1883, ten years before the formation of Algonquin Park, Booth set eyes on the creation of a railroad that would connect Ottawa westwards, running through or near many of his timber limits. Of course, some logs would still have to be transported by river drives, and the railway would not be profitable on timber shipments alone, so Booth considered shipping grain from the Prairies as well.

In 1891, surveying began for the proposed railway, and the first trains travelled the completed Ottawa, Arnprior and Parry Sound Railway in 1896. A railway line through Algonquin Park was not advised by the Royal Commission who were directed to report on the formation of such a park and nature reserve, but they did advocate for lumbermen to have continued access to their limits. The rail line would also prove very important to Park Rangers travelling on patrol and for the shipment of supplies. J.R. Booth and fellow lumbermen also played a major role in supporting the formation of Algonquin Park as a forest reserve which would include the suppression of forest fires, thus protecting the trees that were the source of their revenue.

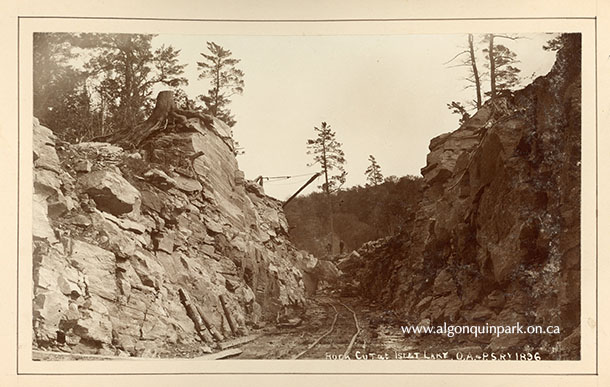

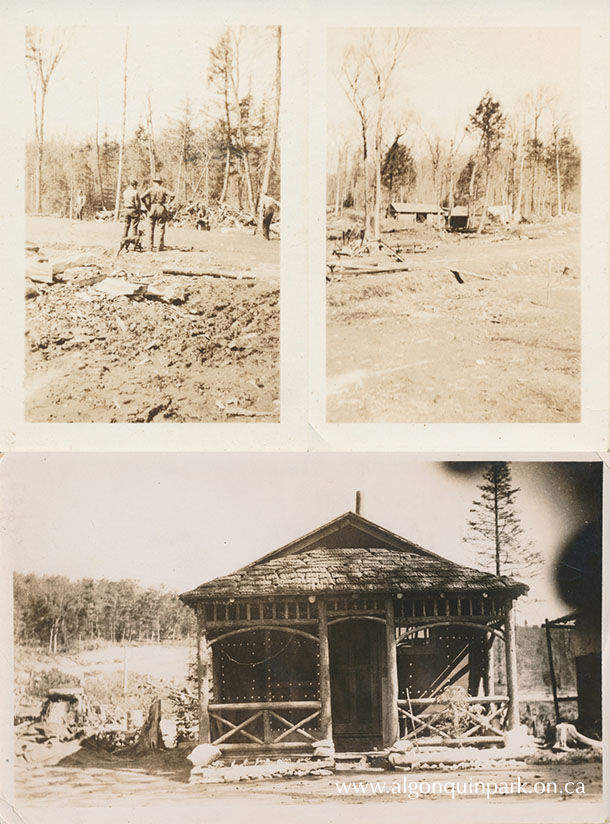

Image: Men working on blasting and clearing a rock cut at Islet Lake, 1896, during construction of the Ottawa, Arnprior and Parry Sound Railway. APPAC, 1976.86.1-54, Photographed by John Walter Le Breton Ross.

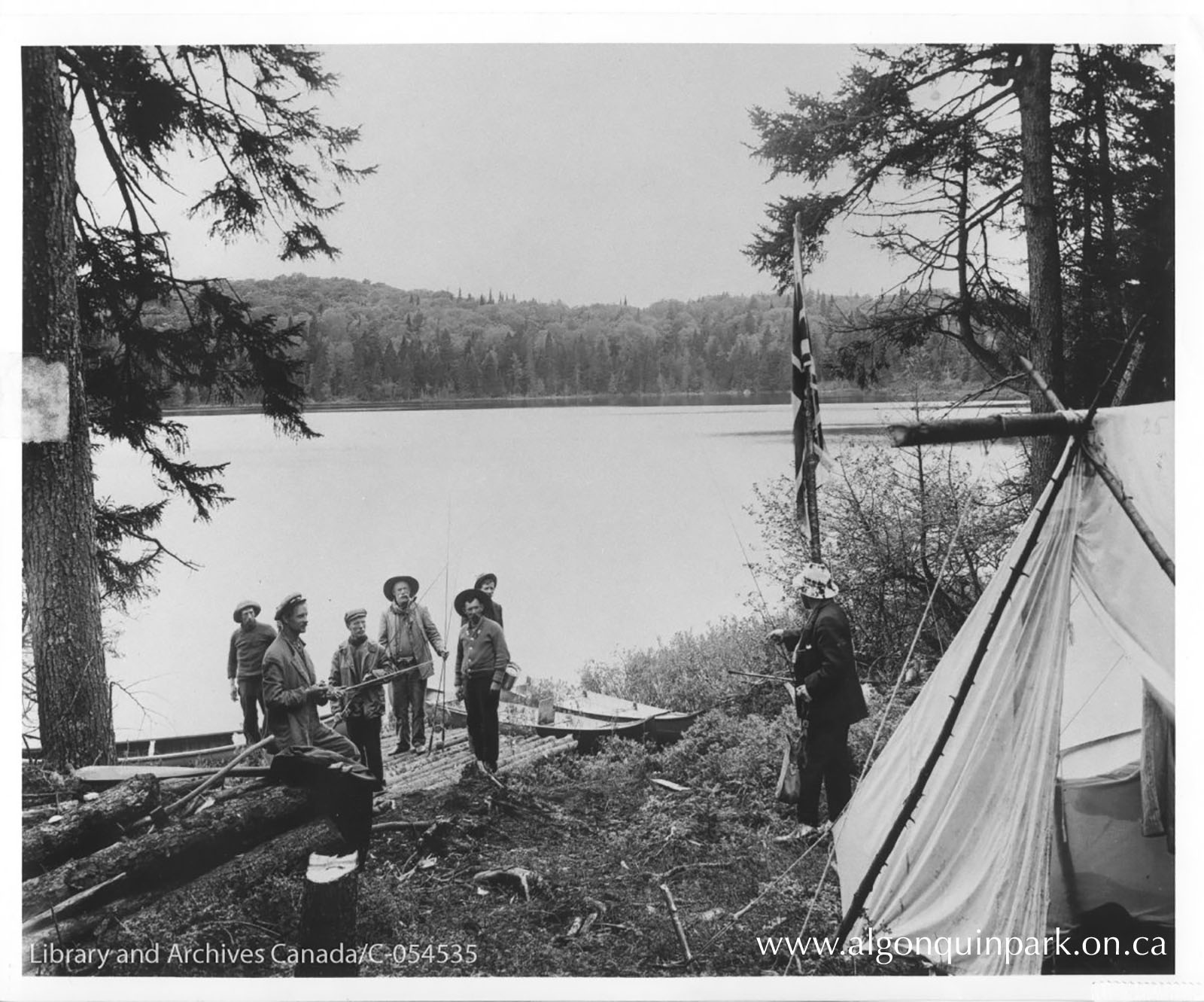

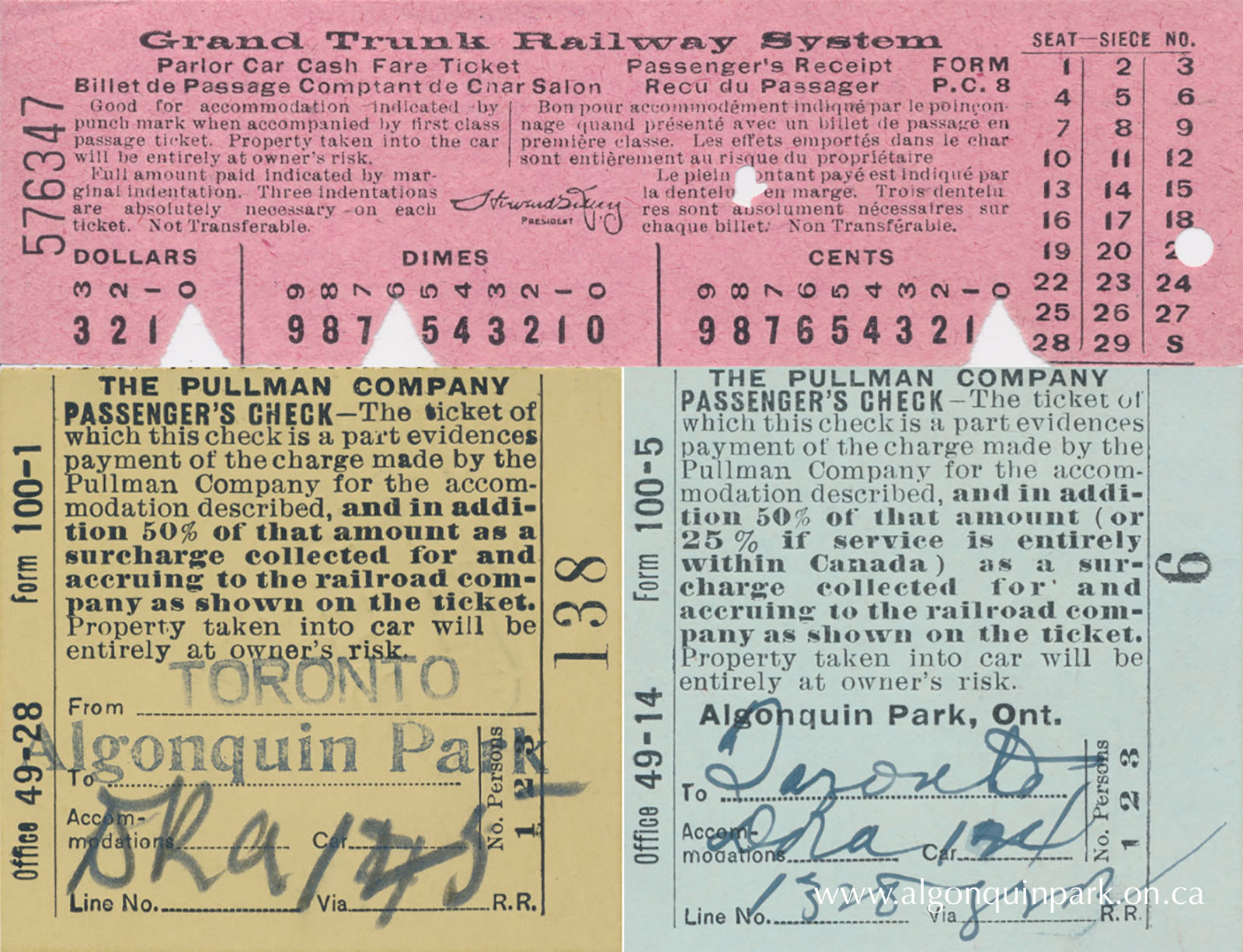

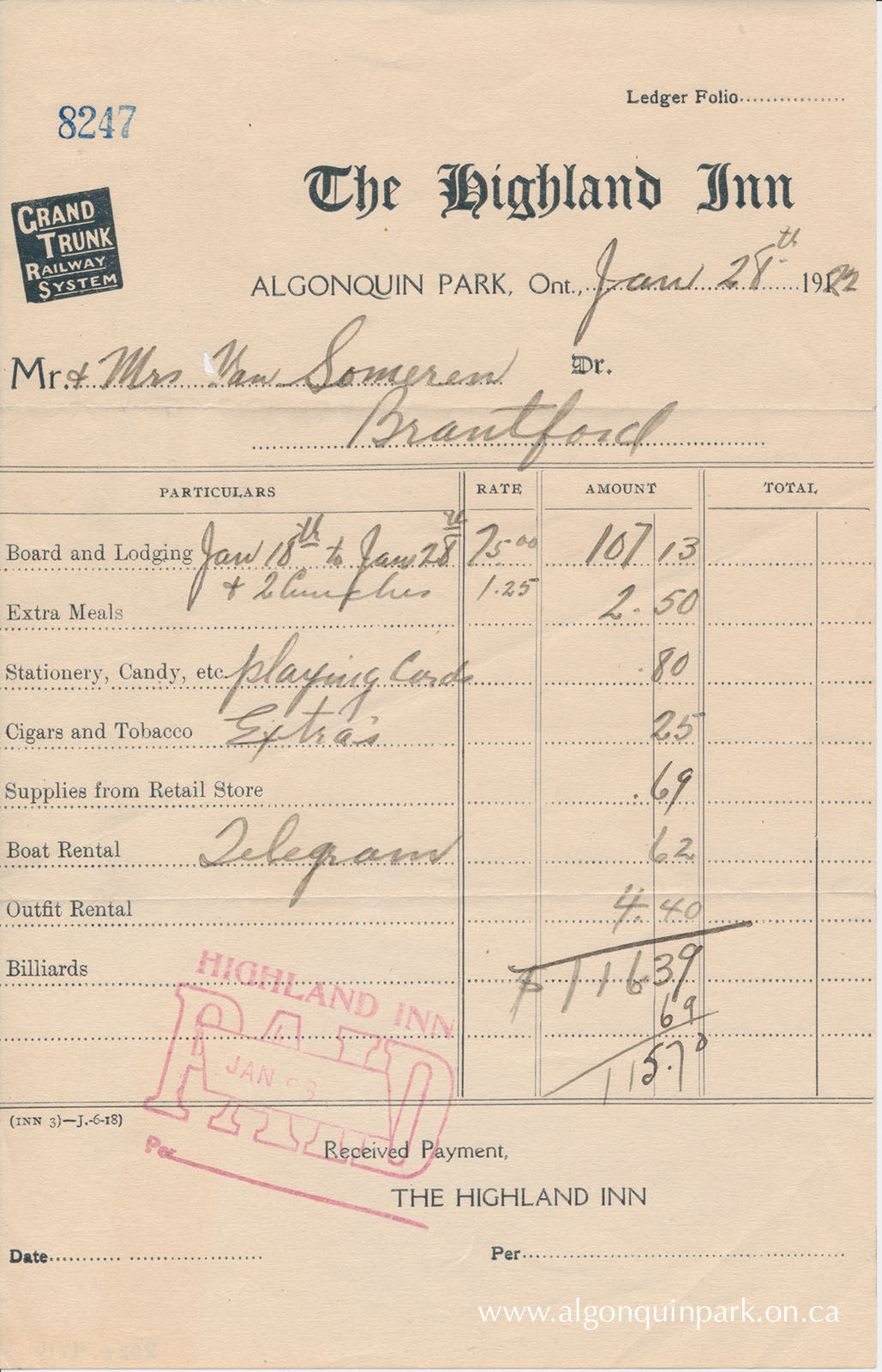

Unbeknownst to Booth, the railroad he created would have a much larger impact on the trajectory of Algonquin Park. Before access by train, the only visitors to Algonquin Park could arrive by bumpy wagon rides or canoe trips. In 1899, the Ottawa, Arnprior and Parry Sound Railway was amalgamated with the Canada Atlantic Railway and was eventually sold to the Grand Trunk Railway in 1905. This sale would lead to a large boost in the tourism and reach of Algonquin Park. Advertised in railway brochures and magazines, Algonquin Park would become a destination for Canadian and international travellers, particularly Americans, seeking the angler’s paradise. Grand Trunk Railway, and later the Canadian National Railway, would operate hotels, such as the Highland Inn, and promote the Park as a destination for rest, relaxation, and recreation, all to boost sales on its passenger trains.

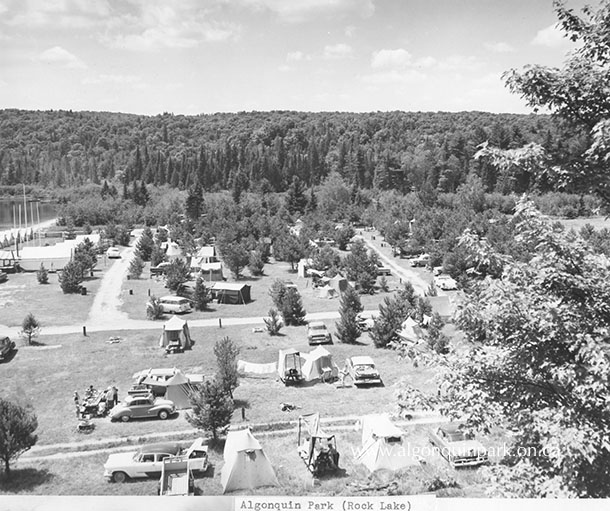

Along the rail line, other lumber companies developed mills and communities grew around them as well as the railroad stations. Families worked and lived in tight-knit communities, raising their families in Algonquin Park. When thoroughfare on the rail line was condemned in the 1930s, the previously discussed construction of a highway was finally undertaken as a depression relief project. Highway 60 roughly followed the route of J.R. Booth’s railway through Algonquin Park, connecting its communities and opening the Park to a new and booming group of recreationalists – the car-campers. Campgrounds, museums, and access points continued to grow along the Highway 60 Corridor to support visitors and travellers. Today, the railroad ties and rails are long gone, but the rail bed continues to be enjoyed by cyclists, hikers, snowshoers, and cross-country skiers as the Old Railway Bike Trail, and Track and Tower Trail.

Image: The construction of Highway 60 paved the way for the boom of car camping and campground Algonquin Park experienced in the 1950s and 1960s. High view of Rock Lake Campground, 1958. APPAC, APM 713.

No person can be entirely characterized as good or evil. Each is a shade of grey, a mixture of the positive and negative traits of their personality and actions. J.R. Booth is no different. MacKay’s book does an exemplary job of exploring all aspects and opinions of Booth’s life and personality. Booth agreed to very few interviews and left no personal recollections behind. To begin the task of getting to know the man himself, MacKay was tasked with searching newspaper articles and quotations of the day as well as listening to the stories of people still living who had once met or heard of Booth. The story that emerged is more often than not a favourable one, with Booth remembered as a man who treated his workers and those in need with respect and kindness.

However, alongside his many charitable deeds, paternal employer instincts, and down-to-earth demeanor, Booth’s life story exhibits his shrewd business decisions and limited environmental consciousness. He contributed to and took advantage of the treatment of Indigenous Peoples in his time. As a lumberman expanding his empire during the square timber period, Booth, alongside his contemporaries, acted with the colonialist invasion and resource extraction of the traditional territories of Indigenous Peoples. With the settlement that followed in the Ottawa Valley and the creation of Algonquin Park, the Algonquins were removed from their land. For Booth specifically, he decided to build the western terminus of his railway at Parry Island, an “Indian Reserve” where his engineers found a natural harbour perfect for large steamships. Booth took advantage of legislation that allowed for the forced purchase of Indigenous lands for railway construction, altering the landscape in service of his enterprise.

Image: J.R. Booth left his mark on more than just logs in the forests of his timber limits. His legacy had a far-reaching impact on the lives of average Canadians as well as the Algonquin Park we know today. Stamping hammer from the J.R. Booth Company, photographed October 28, 1970. APPAC, APM 638.

With the good and the bad, Booth has had long-standing impacts and influences on the industries and people of Ontario and Canada. In Algonquin Park alone, we see remnants of his legacy through geographical landmarks named for him, the remains of lumber camps and farm clearings that dot the landscape, and the abandoned rail line which once rumbled with shipments of grain, timber, and people. A hike at Booth’s Rock Trail gives you a glimpse into his own family’s enjoyment of Algonquin Park and the legacy they have left in the remains of the Rock Lake community. Without Booth’s impact on Algonquin Park, the Park that visitors know today would look and feel very different. For most of his life, J.R. Booth had a great influence on the people and places around him. His life is an interesting story to read and learn from, just like those who paid their respects 100 years ago.

Learn More

Learn more about the Algonquin Provincial Park Archives & Collections

- Explore the online database of photographs, archival records, and artifacts.

- Contact the Collections Coordinator to schedule a research appointment or discuss a donation.

- Read more by purchasing historical publications in The Friends of Algonquin Park’s bookstore.

- Support the Archives with a financial donation via The Friends of Algonquin Park, a Canadian registered charity, to assist us in preserving Algonquin Park's cultural heritage for future generations.

October 12, 2025

Capturing a Moment in Time

Each year, we can only guess at the incredible number of photographs that are captured in Algonquin Park. Is it hundreds of thousands? Perhaps millions?

Whether it’s a quick snap on a cellphone camera, or an edited, high-quality image from professional equipment, we all want to cherish our experiences in this beautiful and inspiring setting. Some may purchase an image or a souvenir from a gift shop but even more will create their own memorabilia.

Whether it’s a quick snap on a cellphone camera, or an edited, high-quality image from professional equipment, we all want to cherish our experiences in this beautiful and inspiring setting. Some may purchase an image or a souvenir from a gift shop but even more will create their own memorabilia.

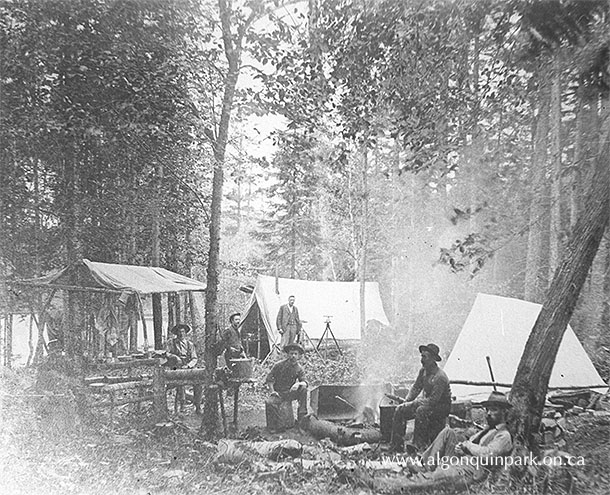

This is a time-honoured tradition. When Algonquin Park was created in 1893, photography, although expensive and difficult, was still a possibility. At the time, photography was mainly used by professionals and Government offices for research, exploration, and surveys. The high cost and tricky development processes meant it was not a hobby that could be enjoyed by everyone. One of the main reasons it was so expensive was that negatives were captured on glass. Beyond the cost, it’s incredible to think that negatives captured on a glass plate could survive to be made into paper prints after surviving the return journey home by railway or canoe, the only transportation options in the Park at the time.

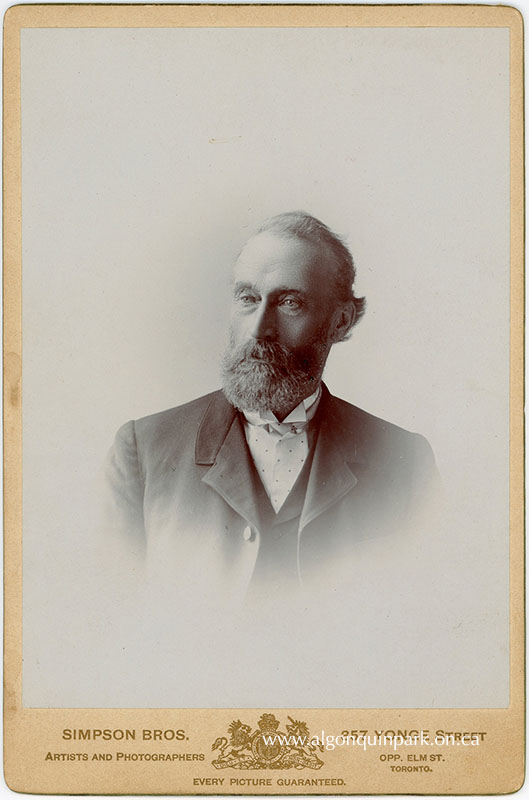

Image: With the high cost and technical expertise needed to operate early camera equipment, photograph studios provided their services to the public. This portrait of Peter Thomson, Algonquin Park’s first Superintendent, was captured sometime between the 1880s and 1895 at the Simpson Bros. studio at 357 Yonge Street, Toronto, Ontario. APPAC, 1976.88.1, H.L. Flood.

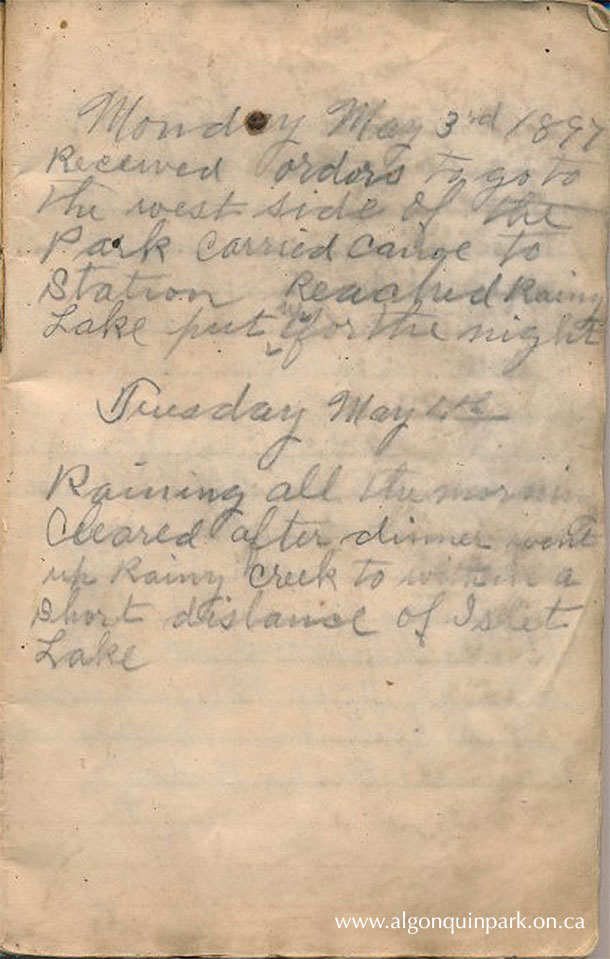

The earliest photograph albums at the Algonquin Provincial Park Archives & Collections (APPAC; “Archives”) date to the 1890s. Two of these were created by John Walter Le Breton Ross, while working on the survey crew for the Ottawa, Arnprior & Parry Sound Railway. These albums showcase images he captured from 1894-1896. His images illustrate the scenery he experienced along the soon-to-be railway line and the work of men and horses labouring to create the railroad tracks and bridges. One of the images is even considered to be APPAC’s earliest selfie. Leaning against a tree in the bottom right of the scene, Le Breton Ross holds a trigger in his hand which activates the camera to photograph himself and his colleagues.

Image: Left – Men and horses work together to drive piles (posts) for a railway bridge at Rainy Lake, 1896. APPAC, 1976.86.1.45, Photographed by John Walter Le Breton Ross. Right – John Walter Le Breton Ross leans against a tree in the foreground with the rest of the survey crew behind him in W.S. Cranston's Camp No. 1 at Cache Lake, 1895. APPAC, 1976.86.1.31, Photographed by John Walter Le Breton Ross.

Over time, the process of photography evolved and changed, as new methods of capturing images and developing negatives were invented. Eventually negatives shifted from glass to plastic mediums, creating a much more affordable and easier to use pastime.

In 1900, the Eastman Kodak Company introduced its mass-market Brownie camera which could be purchased for $1 as an entryway into the world of photography. The company would sell 10 million units in the first five years. The Archives similarly sees a boom in photographs from the 1900s onwards. Park visitors, residents, and staff alike captured images of scenery, wildlife, friends, and family. As a nature reserve, hunting in Algonquin Park was prohibited, but “shooting by camera” was advertised to wildlife enthusiasts. Photographs would become a key advertising technique to entice visitors to the hotels and fishing opportunities of Algonquin Park in the early 1900s.

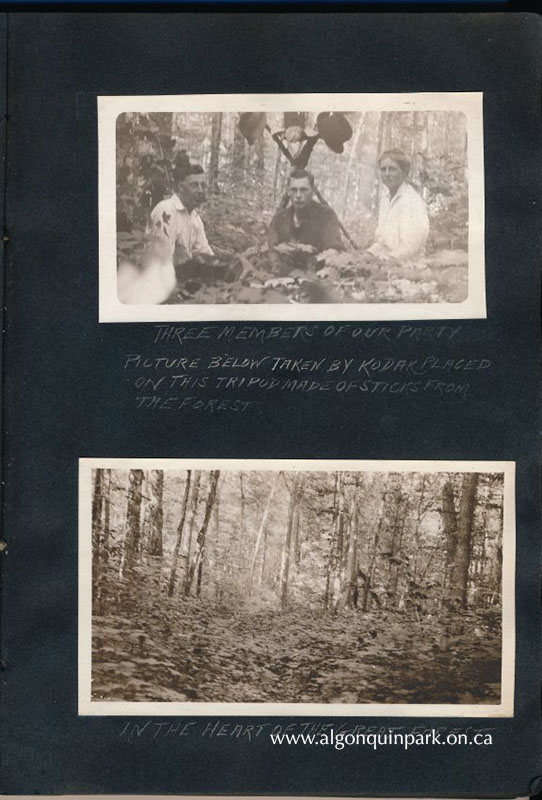

Image: Scrapbook page from album titled “1916 Vacation Scenes Rock Lake, Canada” belonging to Park Ranger Steve Waters. The top image shows three party members sitting in front of a stick tripod with a Brownie camera perched on top. The image below of the forest was taken from this tripod contraption. APPAC, 1998.8.39, From the Collection of Stephen James Waters and Mrs. Albert (Patricia Ware) Swann.

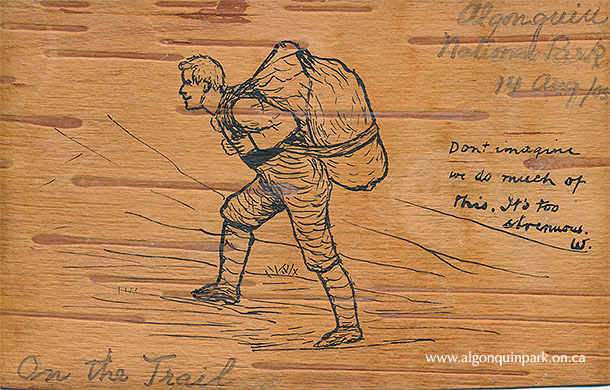

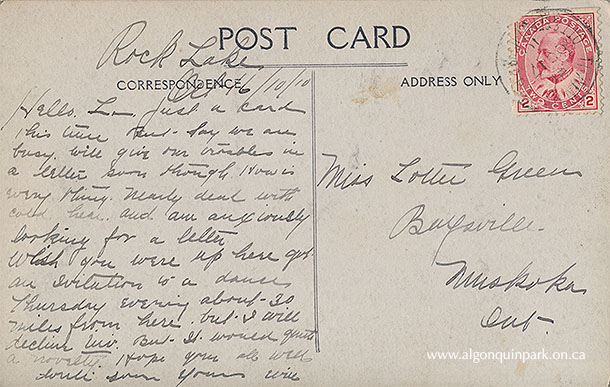

Along with photograph albums, amateur photographers in the early 1900s made their own postcards. Their negatives could be contact printed onto blank postcard stock paper, and the resulting postcard, featuring their very own image, could be mailed to loved ones. One way to tell if a postcard is a “real photo postcard”, and not one mass produced by a printing press, is the relative size of the image to the paper support. In this example below, you can see the image is a little off centre and smaller than the postcard paper.

Image: A “real photo” postcard created by Bert Hancock, auditor and bookkeeper at the Highland Inn. The image shows members of a canoe trip party feeding a deer on a railway platform with their canoe and packs nearby. The reverse is postmarked 1908. APPAC, 2023.3.24, Collection of Don Beauprie.

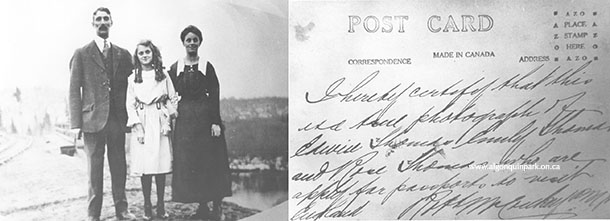

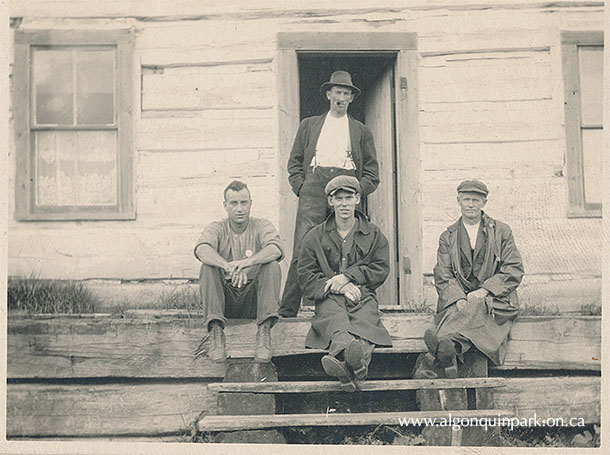

Photographs and postcards were also used as a means for identification. In the rural communities of Algonquin Park, residents relied on their tight knit communities to produce pieces of identification. This photograph of the Thomas family was taken and turned into a postcard by ‘Bert’ Hancock, who worked as bookkeeper and auditor for The Highland Inn. The postcard was taken to the nearest Justice of the Peace to certify their identities so they could apply for passports to England.

Image: Front and reverse of postcard used by the Thomas family to apply for passports to England, in 1920. Edwin and Emily Thomas lived with their daughter Rose at Canoe Lake. APPAC, 1972.3.32-33, Thomas and Wilkinson.

As technology advanced, photography became more accessible with added features. Cameras began to have manual exposures, f stops, and light meters. With all of these features, photography could be difficult to learn, and in many urban centres, enthusiasts created camera clubs. Camera clubs and conventions allowed people to experiment and learn about photography.

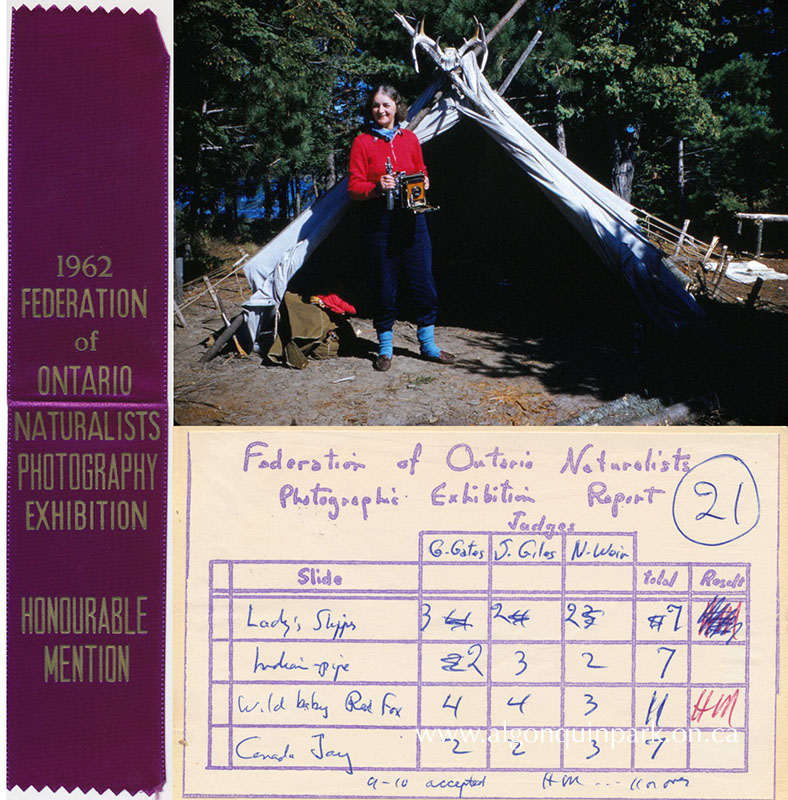

The Thomas and Wilkinson Collection at APPAC includes some special pieces which illustrate these camera clubs. Below is a score card used to adjudicate Rose Thomas’ submission to the “Federation of Ontario Naturalist Photographic Exhibition”. Participants of this photography exhibition submitted four prints to three judges who recorded their scores on the card. Within these clubs and exhibitions women were fairly welcomed, and even residents from rural settings could join. After moving from Canoe Lake, the Thomas family, together with their relative Jack Wilkinson, were the proprietors of Kish-Kaduk Lodge on Cedar Lake in the northern part of Algonquin Park. For her submission of “Wild baby Red Fox”, Rose Thomas received an honourable mention, and her ribbon is present in the Archives’ collection.

Image: Rose Thomas poses with her camera in front of a canvas tent, c. 1950s – 1970s. The scorecard for her submissions to the 1962 Federation of Ontario Naturalists Photographic Exhibition was mailed to her at Kish-Kaduk Lodge, Algonquin Park. She received this Honourable Mention ribbon for her submission of a photograph of a baby Red Fox. APPAC, 1972.3.109.33,1972.3.246, 1972.3.247, Thomas and Wilkinson.

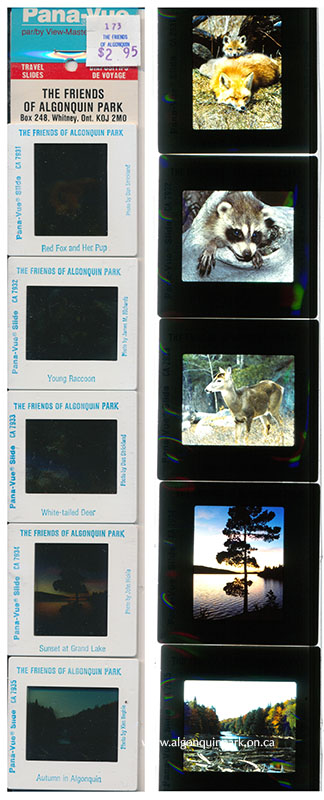

As for colour photography, its earliest days trace back to the late 1800s, but colour film did not become readily available to the average consumer until the 1930s. Even then, colour images did not become popular until a few decades later. When colour photography finally became all the rage, so did the 35mm transparency slide. Unlike negatives, which are the reverse of an image, these slides were positive films and often housed in plastic or cardboard mounts. They could be arranged in slide carousels and projected onto a screen or wall using a slide projector. Travellers returning home from exciting adventures could curate and present their images to friends and families. At The Friends of Algonquin Park bookstore, if you missed out on a certain wildlife spotting or scene with your own camera, you could purchase a set of slides to add to your collection.

Image: Visitors to The Friends of Algonquin Park bookstore could select from a variety of slide sets to add to their collection. This set of five Pana-Vue by View-Master slides features images of "Red Fox and Her Pup"; "Young Raccoon"; "White-tailed Deer"; "Sunset at Grand Lake"; and "Autumn in Algonquin". APPAC, 2024.7.10.

Today we enjoy the vast leaps and bounds available to us with digital photography. No longer limited by the number of exposures on a single roll of film, today’s camera hunter is free to snap as many images of that elusive bird or mammal as they please, until they dwindle down the number of megabytes remaining on their storage device. Although technology has changed in truly unrecognizable ways to those who enjoyed it over 100 years ago, it's clear that the need to capture and document our lives and beautiful spaces, such as Algonquin Park, will always be timeless.

Learn More

Learn more about the Algonquin Provincial Park Archives & Collections

- Explore the online database of photographs, archival records, and artifacts.

- Contact the Collections Coordinator to schedule a research appointment or discuss a donation.

- Read more by purchasing historical publications in The Friends of Algonquin Park’s bookstore.

- Support the Archives with a financial donation via The Friends of Algonquin Park, a Canadian registered charity, to assist us in preserving Algonquin Park's cultural heritage for future generations.

September 27, 2025

Colouring Algonquin Park

Tom Thomson, the iconic Canadian artist, is well known for his colourful renditions of the Algonquin Park landscapes so many canoeists and visitors cherish. His love for Algonquin Park is felt through each brushstroke and the impressions he left on those who knew him. He introduced his fellow artists, including the future members of the Group of Seven, to the Park, and his art continues to inspire artists and draw visitors today.

Tom Thomson, the iconic Canadian artist, is well known for his colourful renditions of the Algonquin Park landscapes so many canoeists and visitors cherish. His love for Algonquin Park is felt through each brushstroke and the impressions he left on those who knew him. He introduced his fellow artists, including the future members of the Group of Seven, to the Park, and his art continues to inspire artists and draw visitors today.

But in his time, Thomson was just beginning to receive recognition for his work when he met his untimely fate in Canoe Lake on July 8, 1917. Although ruled accidental drowning, the circumstances surrounding his disappearance, death, and burial continue to draw speculation. Canoeists exploring Canoe Lake can visit a stone cairn crafted by his friends and fellow artists. A replica of the memorial is on display at the Algonquin Park Visitor Centre.

Image: A display in the cultural history exhibits at the Algonquin Visitor Centre highlights the life and works of Tom Thomson. A bust of the artist, sculpted by Sandra J. Shaw, sits above a replica of the stone cairn which is located on Canoe Lake.

Although perhaps the most recognizable and well-known artist connected with Algonquin Park, Tom Thomson is only one of the many who have captured their experiences in these landscapes. For the Algonquin Provincial Park Archives & Collections (APPAC; “Archives”), their work offers a priceless gift to the Park’s history: a glimpse of the Park in colour.

Image: Barbara Caldwell and Robert Bateman, Algonquin Wildlife Research Station, 1949. Bateman stands holding a paint brush next to an easel with a landscape painting in progress. His supplies are visible on the ground behind them. APPAC, x2024.8.2.1.

Before the advent and slow rise of popularity of colour photography, the world was captured in black and white. Through numerous donors, the Archives is fortunate to preserve and share a vast photographic collection that illustrates all aspects of Algonquin Park’s history, but the colours in these scenes are left to the imagination.

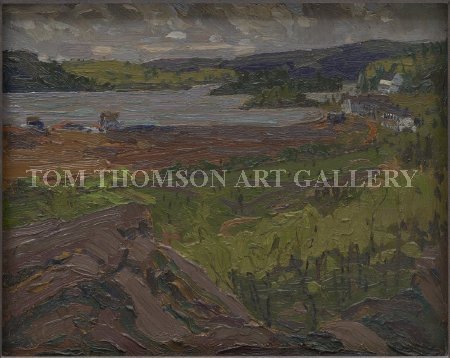

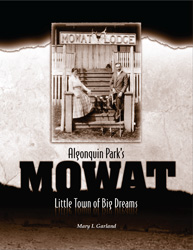

Take for instance this photograph of Mowat taken from the village cemetery. Along the shore of Canoe Lake, we can see Mowat Lodge, Blecher's cottage, and other buildings, as well as the remains of the chip yard of the old Gilmour Lumber Company operations. If we were there over 100 years ago when this photograph was captured, we would know the array of colours it represents.

Image: View of Mowat and Canoe Lake from the cemetery, c. 1910s. APPAC, 1995.1.3, Harry and Adele Ebbs.

Tom Thomson helps us visualize what residents and visitors experienced all those years ago. The Tom Thomson Art Gallery in Owen Sound holds a sketch painted by Tom Thomson from a very similar vantage point. His sketch captures the moody sky and lake on the day he sat down to paint the landscape. The white buildings peek out from around the lake, and the brown helps us understand the location of the old logging company’s chip yard.

|

| Buy Algonquin Park's Mowat: Little Town of Big Dreams |

“Canoe Lake, Mowat Lodge”, by Tom Thomson, Summer 1914. Oil on plywood. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, 1988.011.122, Gift from an anonymous donor through the Ontario Heritage Trust, an agency of the Government of Ontario, 1988.

In addition to paintings and drawings, artists would sometimes modify black and white images to create colour photographs. Glass lantern slides and photographic prints could be hand-coloured with paint to illustrate the scene. This technique adds a smattering of colour to an almost entirely black and white collection of early photographs in the Archives.

Image: A collection of painted glass lantern slides, c. 1920s – 1940s. An artist has added colour to the original black and white images captured by the camera. Clockwise from top left: three men sit around a fire at their campsite; the view of Cache Lake from the fire tower at Skymount; the docks and buildings of Camp Ahmek, Canoe Lake; “Billy the deer” standing with Joe Lake Station in the background. APPAC, 1976.98.44-47, Collection of Luta and Fletcher Calvert.

One question remains – are these colours accurate? Many artists are devoted to capturing their worlds as accurately as they see them. Mark Robinson’s diary entries and recollections tell us that Tom Thomson was persistent in experimenting with pigments to capture colours such as the grey of an aged stump or the brown of a changing fern.

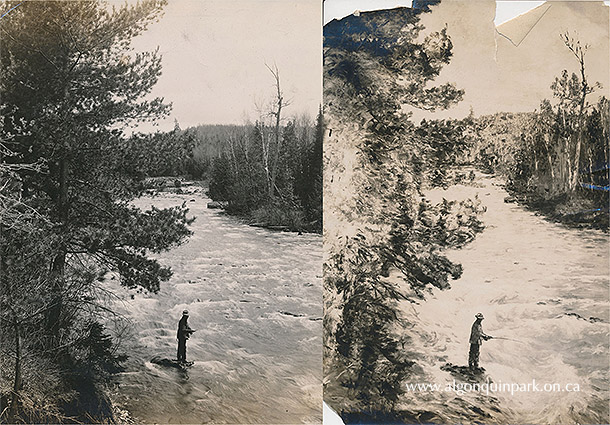

For those works that might have been created at home or in the photo studio days, months or years after visiting the Park, the colours may be less accurate. In 1925, V.B. Gray, editor of the Rod and Gun Canada magazine, and his fishing party took many black and white photographs as part of their trip through the northern reaches of Algonquin Park. One of these images was the basis for a painting created shortly after the trip and destined to hang in the Canadian National Railway’s New York City office building. When writing to V.B. Gray on November 16, 1925, W.S. Thompson, Director of Publicity, notes the painting “is a striking bit of color except that the water is a little bit too light a shade of blue for Algonquin.” Fortunately for the Archives, Thompson mailed a black and white photograph of the painting to Gray, which can be compared to its muse, but the fate of this painting and its wonderful colours is unknown.

Image: Left – Original photograph of V.B. Gray fly-fishing in White Partridge River, 1925. Right – Black and white photograph of a colour painting sent to V.B. Gray by W.S. Thompson, Canadian National Railway, November 16, 1925. APPAC, x2024.4.1-77.

Whether an accurate depiction or a piece of artistic liberty, the colourful product aids the Park’s history in many ways. If accurate, it provides insight to the colours used and seen by people of that time, and even if slightly altered, the colours remind us that the vibrancy and beauty of the Algonquin Park remains an alluring quality for all who experience it.

Learn More

Learn more about the Algonquin Provincial Park Archives & Collections

- Explore the online database of photographs, archival records, and artifacts.

- Contact the Collections Coordinator to schedule a research appointment or discuss a donation.

- Read more by purchasing historical publications in The Friends of Algonquin Park’s bookstore.

- Support the Archives with a financial donation via The Friends of Algonquin Park, a Canadian registered charity, to assist us in preserving Algonquin Park's cultural heritage for future generations.

August 20, 2025

Your Guide to Algonquin Park

Image: Cover of the 2025 Algonquin Park Information Guide.

Extra, extra! Read all about it!

First time and frequent visitors alike start their trip to Algonquin Park by picking up the latest “Algonquin Information Guide”, published by The Friends of Algonquin Park. This handy newspaper features all of the campground, reservation, safety, regulation, and program information that visitors need to plan and make the most of their adventures in Algonquin Park.

First time and frequent visitors alike start their trip to Algonquin Park by picking up the latest “Algonquin Information Guide”, published by The Friends of Algonquin Park. This handy newspaper features all of the campground, reservation, safety, regulation, and program information that visitors need to plan and make the most of their adventures in Algonquin Park.

But the information guide visitors know today hasn’t always looked this way, with its newsprint texture, modern photography, and standardized format.

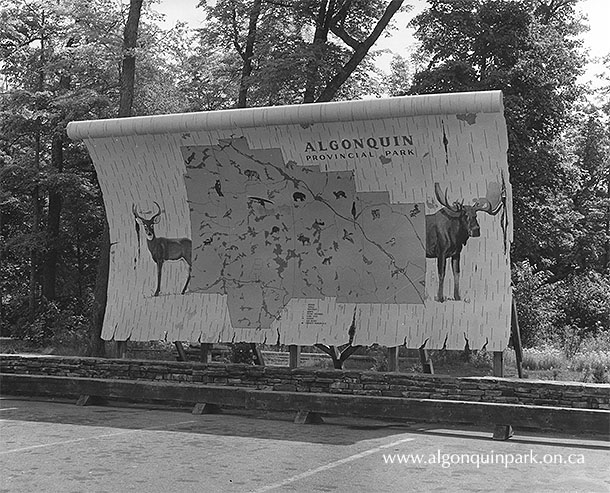

As part of its archival collection, The Algonquin Provincial Park Archives & Collections (APPAC; “Archives”) contains a large collection of Algonquin Park information guides in all shapes and sizes. These documents not only show how information guides have changed and evolved over time, but they also provide a valuable insight into the Park’s history including changes to campgrounds, access, transportation, facilities, programs, and recreational practices.

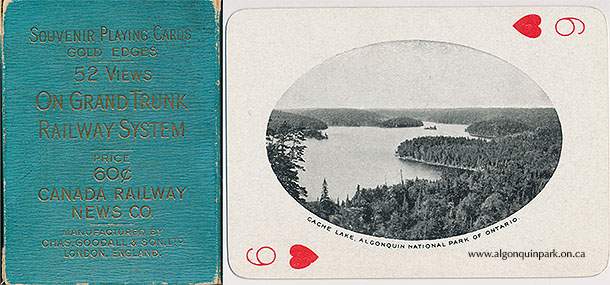

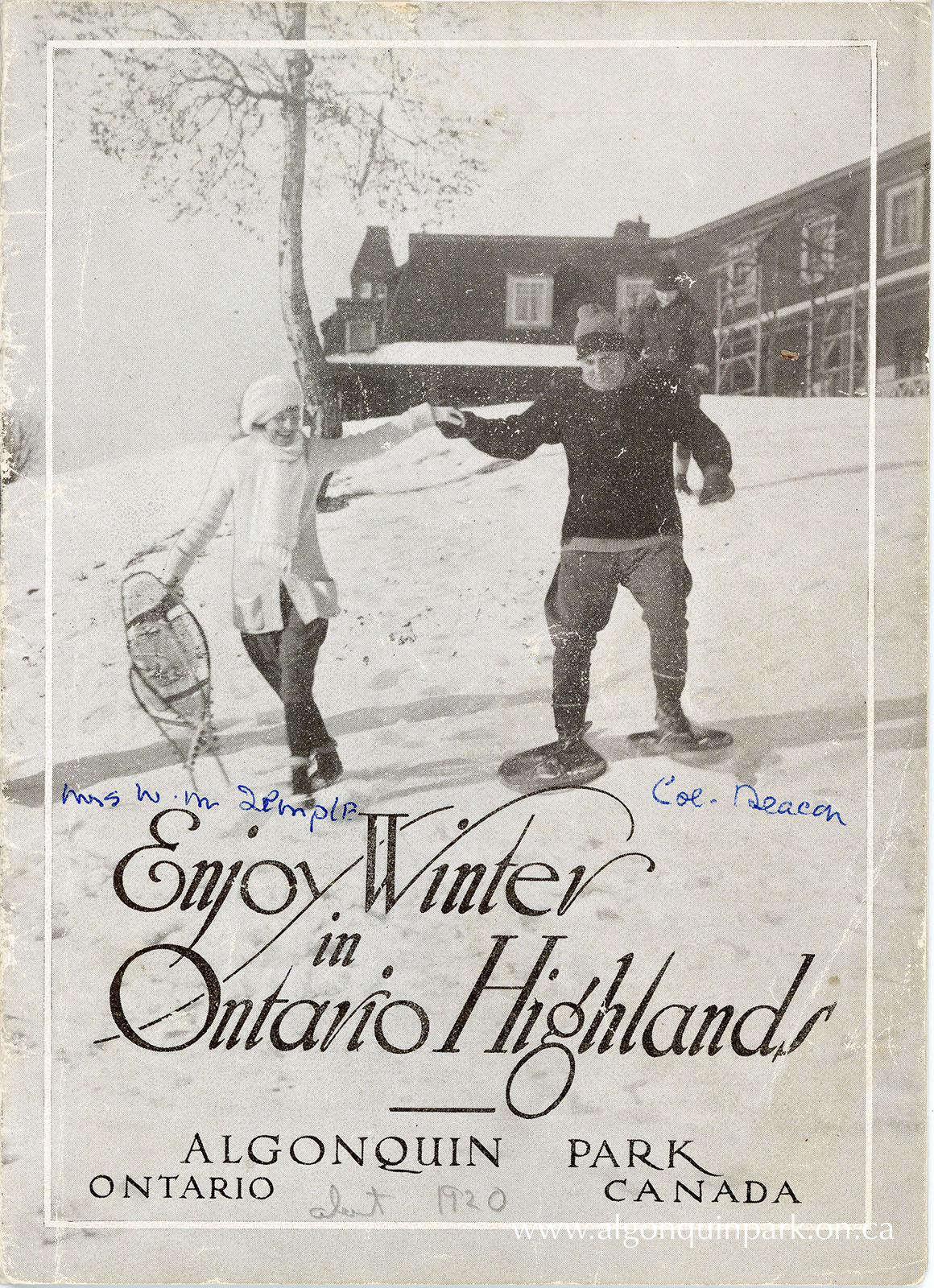

In the early days of Algonquin Park, advertising and information was produced by the railway companies who hoped to allure visitors to the Park and in turn sell passengers train tickets and stays in their hotels. Their maps and booklets offered prospective visitors a glimpse of the attractions that awaited them and the information needed to plan their trip.

Image: Back and front cover of an advertising booklet titled “Algonquin Park” “The Region for Health and Happiness” published by Canadian National Railways, 1924. The Highland Inn, tents, and a cottage are visible in the background of two couples happily fishing and canoeing. APPAC, I-4-1c.

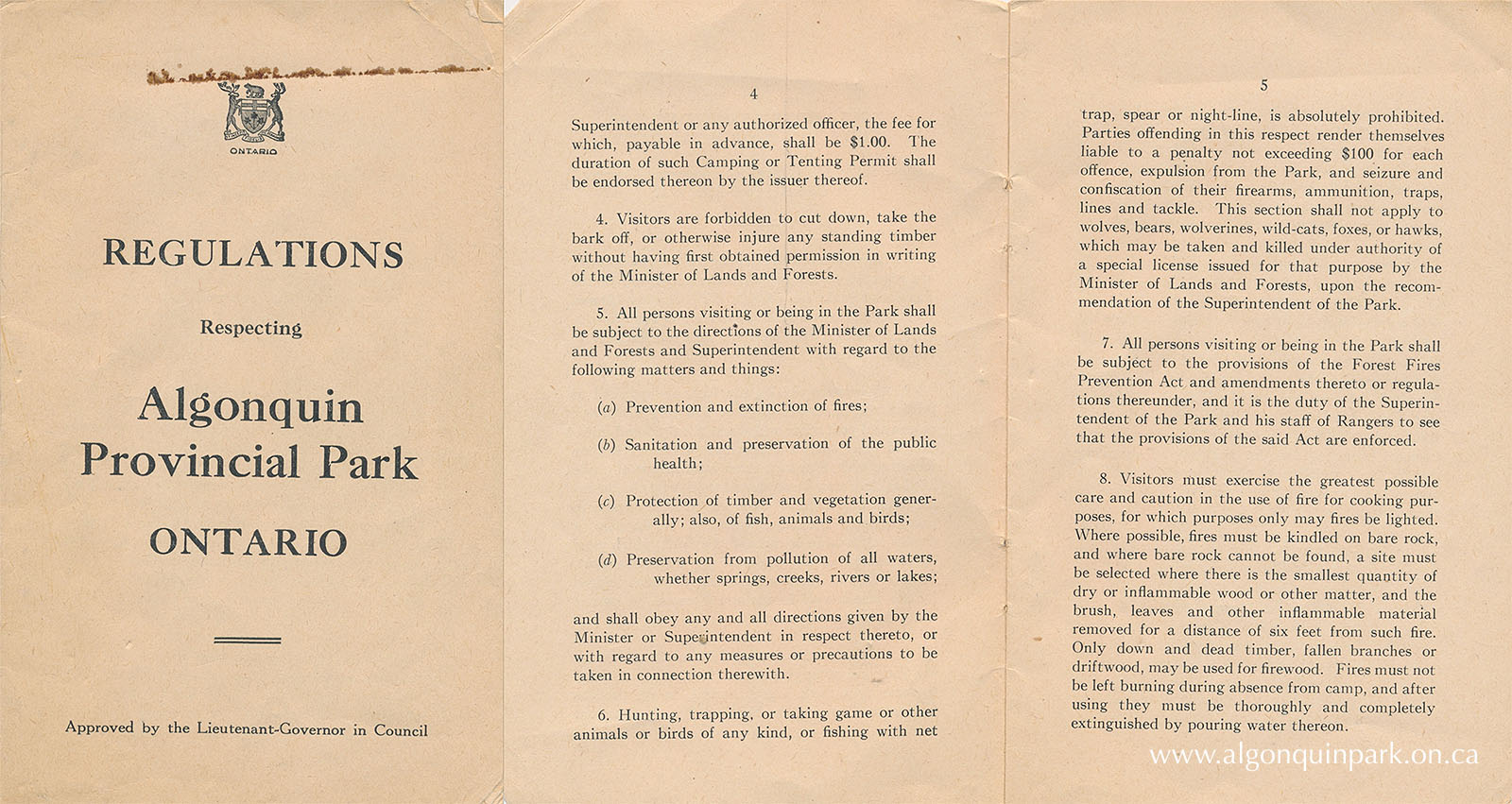

In stark contrast, the Archives’ earliest “information guide” published by the Government of Ontario is the 1920 all text, no pictures booklet listing 29 “Regulations Respecting Algonquin Provincial Park Ontario”. By 1931, the booklet had been updated to include 43 regulations. Then, like today, visitors were required to obtain travel permits, camping permits, and fishing permits for their visits. This booklet outlined the rules, fees, and responsibilities for those visiting and working in Algonquin Park.

Image: Cover and pg. 4-5 of “Regulations Respecting Algonquin Provincial Park”, published by the Government of Ontario, 1931. APPAC, E-7-6a.

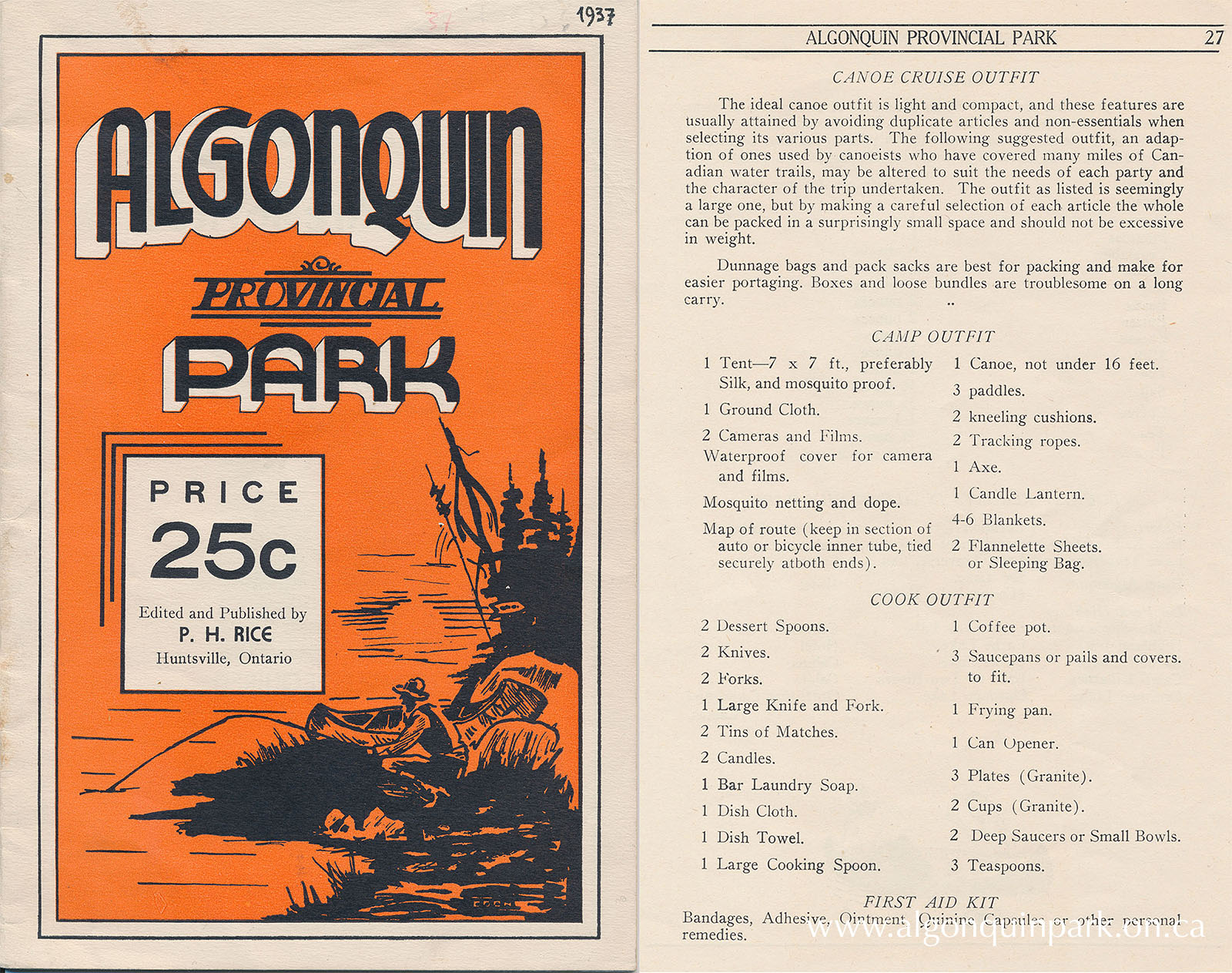

At the same time, local publishers were selling their own guides, providing more information and advice then the bare bones government regulations. This 1937 “Algonquin Provincial Park” booklet published by P.H. Rice of Huntsville, Ontario includes advertisements from the Government of Ontario and local businesses alongside various trip planning information. The booklet describes the history and environment of Algonquin Park, illustrates various canoe routes, provides transportation and regulation information, and places emphasis on the wildlife and fishing opportunities.

Image: Cover of “Algonquin Provincial Park” by P.H. Rice, Huntsville, Ontario, 1937 with sample page. Page 27 provides suggestions for the ideal canoe outfit to be packed for a trip. Information guides provide not only a glimpse into how the Park was at the time of publication, but also the recreational practices and equipment. APPAC, 2023.3.60, D. Beauprie.

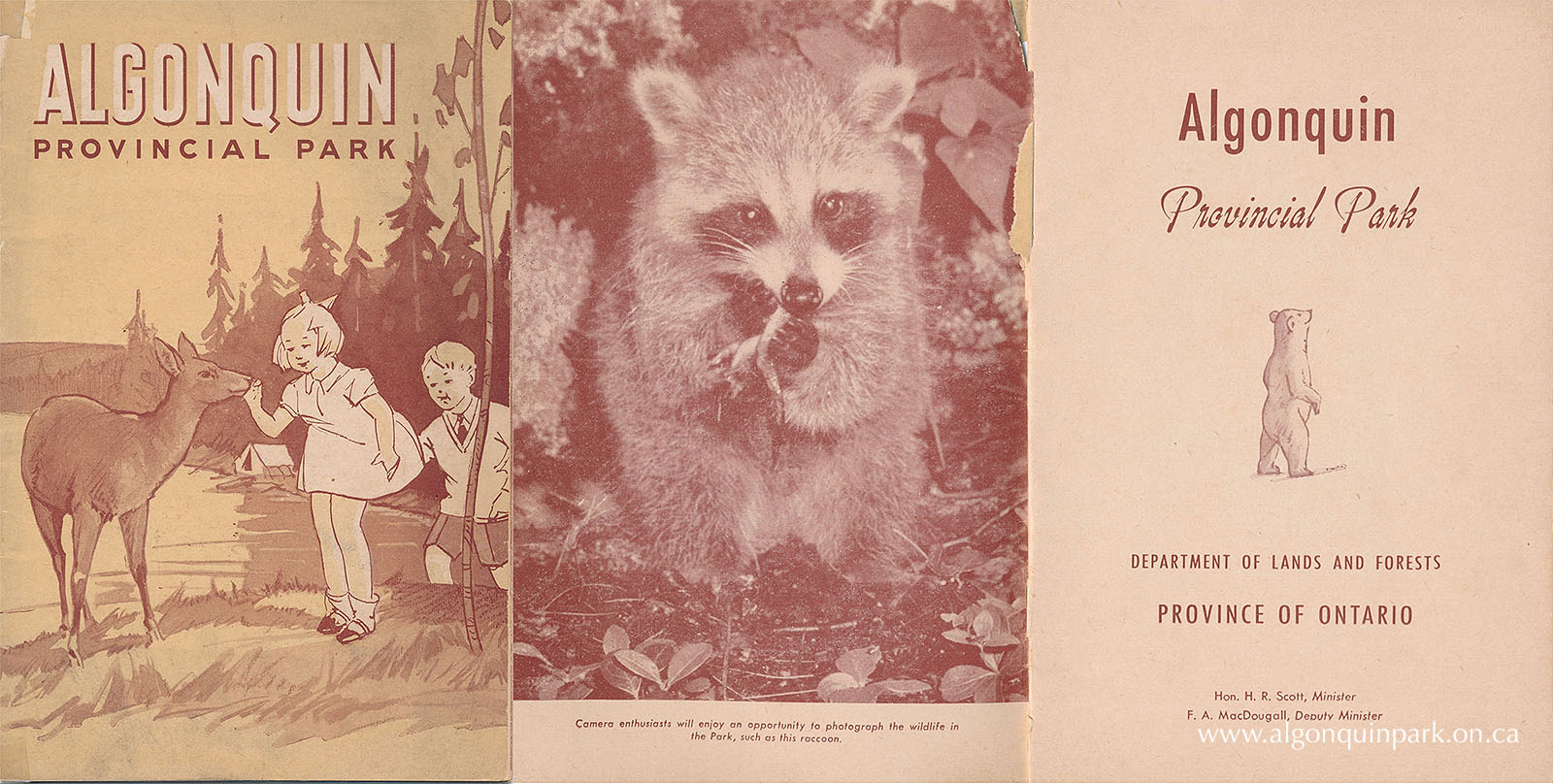

In time, the Ontario Department of Lands and Forests, the ministry that once managed the Provincial Park system, began to produce its own booklets intended to attract potential visitors and provide information for their trips. Artwork and photographs in this 1949 booklet illustrate the activities visitors could enjoy and the wildlife they could expect to see during their visit.

Image: Cover and first pages of “Algonquin Provincial Park” published by the Department of Lands and Forests, c. 1949. Among the outdoor recreationalists, photography enthusiasts were encouraged to visit Algonquin Park to capture its wildlife, “such as this raccoon.” APPAC, 2023.3.59, D. Beauprie.

The booklet describes the beauty of the environment and opportunities available to anglers. A description of fisheries management and a list of the lakes closed in alternating years helped anglers plan their canoe routes. Today the text provides modern researchers a look at the history of conservation practices and experiments in Algonquin Park.

The booklet also advertises Algonquin Park’s first public campground, Lake of Two Rivers Campground, which first opened in 1938. With the booming popularity of car-camping in the 1950s, more campgrounds were cleared and expanded to meet the demand.

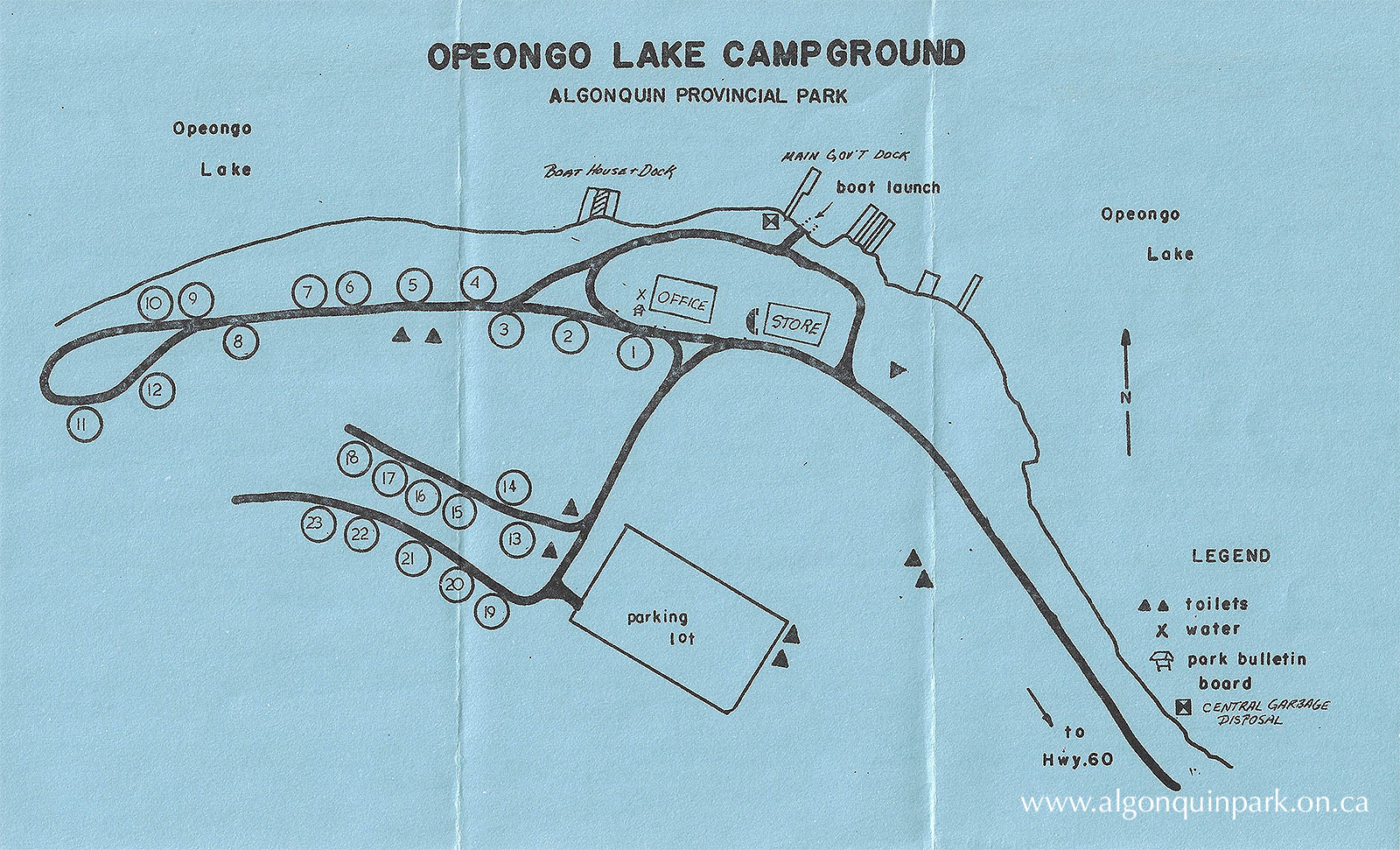

The Ontario Department of Lands and Forests, and its successor, the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (formed in 1972), continued to publish booklets, and later shorter leaflets and brochures. APPAC holds select examples from the 1950s and 1960s and a comprehensive collection of brochures beginning with the 1970s. Generalized Algonquin Park brochures were supplemented by specific campground brochures. The Archives holds brochures for Tea Lake, Lake of Two Rivers, Mew Lake, Canisbay Lake, Pog Lake, Kearney Lake, Rock Lake, and Raccoon Lake Campgrounds from 1983 - 2003, and Opeongo Lake Campground from 1983 – 1985.

Image: Map from the Opeongo Lake Campground brochure, 1983. The campground was permanently closed in 1987. APPAC, M-17-1j.

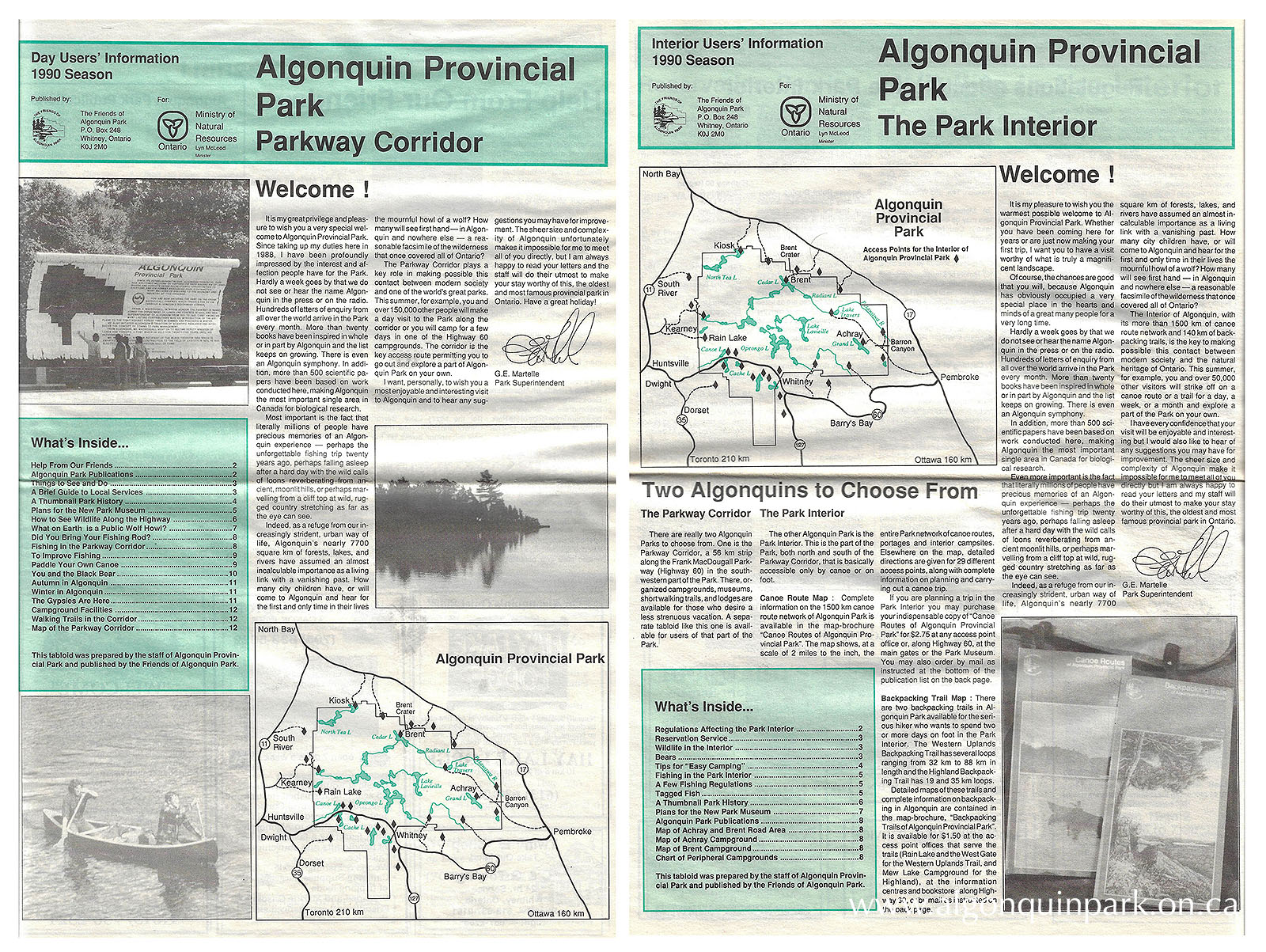

The newspaper style of information guide known today first arrived on the scene in 1990. Two information guides, “Parkway Corridor: Day Users’ Information” and “The Park Interior: Interior User’s Information” were published in English and French by The Friends of Algonquin Park for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. The Friends of Algonquin Park were first formed in 1983 to reprint government publications, such as the canoe routes map, so that proceeds could be directly reinvested into Algonquin Park. Their publication role has grown and evolved since then, and the charity supports a variety of initiatives to support the educational and interpretive programs of Algonquin Park.

Image: Cover pages of the 1990 information guides: “Parkway Corridor” and “The Park Interior”. APPAC, M-15-1a; M-15-1c.

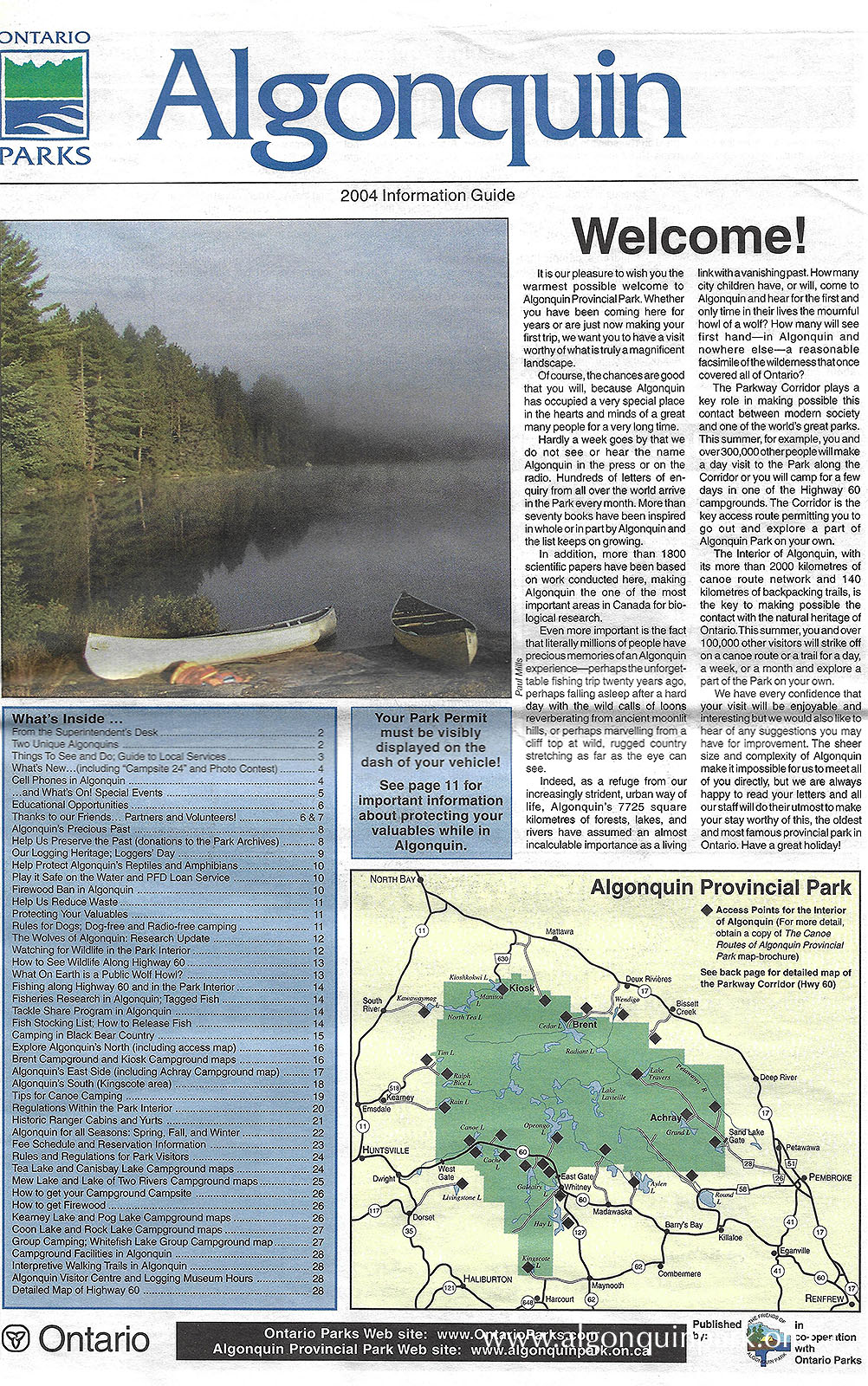

Like today’s information guide, these early newspapers included news from the Park and information about regulations, reservations, events, wildlife, and safety. In 2003, the two newspapers would be combined into the “Algonquin Information Guide” and mark the last year the campground leaflets were separate from the guide. In 2004, readers could find all of the campground, corridor, and interior information they needed in one handy resource.

Image: Cover of the 2004 “Algonquin Information Guide” – the first year all of the Park’s information was compiled into one handy resource. APPAC, M-15-2x.

Each and every year, APPAC continues to preserve copies of the information guide as well as a variety of other Algonquin Park publications. They also appreciate the support of donors who help to fill in the gaps of the earliest publications. Collecting today’s materials preserves Algonquin Park history for future generations, just as collecting the past supports our growing understanding of how Algonquin Park was enjoyed, managed, and advertised.

Learn More

Learn more about the Algonquin Provincial Park Archives & Collections

- Explore the online database of photographs, archival records, and artifacts.

- Contact the Collections Coordinator to schedule a research appointment or discuss a donation.

- Read more by purchasing historical publications in The Friends of Algonquin Park’s bookstore.

- Support the Archives with a financial donation via The Friends of Algonquin Park, a Canadian registered charity, to assist us in preserving Algonquin Park's cultural heritage for future generations.

July 29, 2025

The Last Stand: White Pine Nature Reserves in Algonquin Park

Each year, researchers who call Algonquin Park their laboratory share their research with visitors at Meet the Researcher Day. This event, hosted in partnership between the Algonquin Wildlife Research Station; The Friends of Algonquin Park; Ontario Parks; and Harkness Laboratory of Fisheries Research, allows curious minds to ask questions of those who study reptiles and amphibians, birds, small mammals, fish, wolves, and even humans (through archaeology).

Each year, researchers who call Algonquin Park their laboratory share their research with visitors at Meet the Researcher Day. This event, hosted in partnership between the Algonquin Wildlife Research Station; The Friends of Algonquin Park; Ontario Parks; and Harkness Laboratory of Fisheries Research, allows curious minds to ask questions of those who study reptiles and amphibians, birds, small mammals, fish, wolves, and even humans (through archaeology).

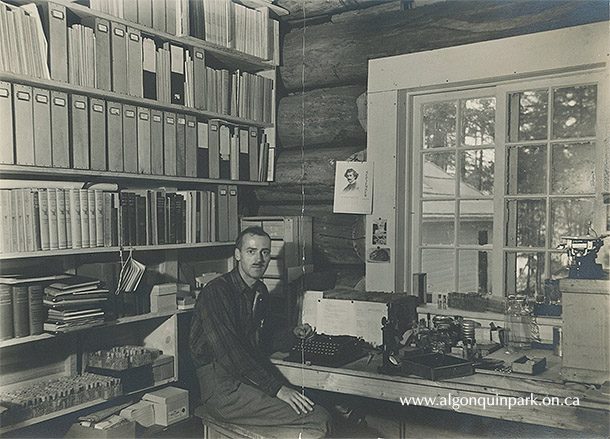

In honour of this year’s Meet the Researcher Day, the Algonquin Provincial Park Archives and Collections (APPAC; “Archives”) is highlighting a researcher who like many others was influenced by his early time in Algonquin Provincial Park. Duncan MacLulich was a student at the University of Toronto when he came into the Park to complete field research in the 1930s. This formative time influenced his passion for ecology and ecosystem preservation throughout his life and career.

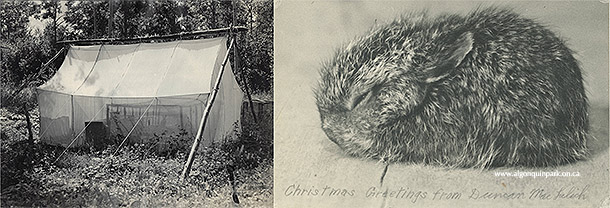

Image: Left - “Field Office” of D. MacLulich during his Varying Hare study, c. 1930s. APPAC, 1977.9.186. Right - Christmas card from MacLulich during his Snowshoe Hare study, c. 1930s. APPAC, 1977.9.234. From the life works and personal possessions of Dr. Duncan A. MacLulich (from daughter M.A. Capstick).

In the 1930s, MacLulich was a student studying forest ecology and later the population of Snowshoe Hare in Algonquin Park. For researchers at this time, the Park was important due to the many opportunities to study animals and environments that had been relatively untouched by humans. However, there were few research facilities available to researchers in Algonquin Park at this time. The one and only in the 1930s was the Ontario Fisheries Research Laboratory (OFRL) which opened a station on Lake Opeongo in 1936.

In exchange for helping haul nets and measure fish, MacLulich, and other researchers, were able to live and work in the Park and run their own field research. MacLulich described the lab as “having a broad view of their responsibility to biology as a whole”. These early years conducting research within the Park and in the Ontario wilderness led MacLulich to create lasting relationships with not only the people in the Park but with the environment as well.

Image: D.A. MacLulich pictured sitting in the Ontario Fisheries Research Laboratory, at Lake Opeongo, 1938. APPAC, 1977.9.229. Donated from the Collection of Dr. Duncan A. MacLulich by daughter M.A. Capstick

|

Make a charitable donation to assist us in protecting Algonquin Park's cultural heritage for future generations. |

After graduating from the University of Toronto, MacLulich was offered a job as a Park Ranger in Algonquin Park by Superintendent Frank MacDougall.

Superintendent MacDougall believed that it was essential to have biology research within the Park although no such positions existed on Park Staff at the time. MacLulich was hired as a ranger and given ranger duties while being encouraged to do research on the side. The Archives also consider him to be the first Park Naturalist on staff, setting out the first interpretive trail on the Canisbay Lake portage in 1938. In addition to his duties, MacLulich completed studies on animal populations and was asked to run a trout parasite survey by Professor Harkness of the OFRL. He covered 7 watersheds and several lakes, sampling Brook Trout.

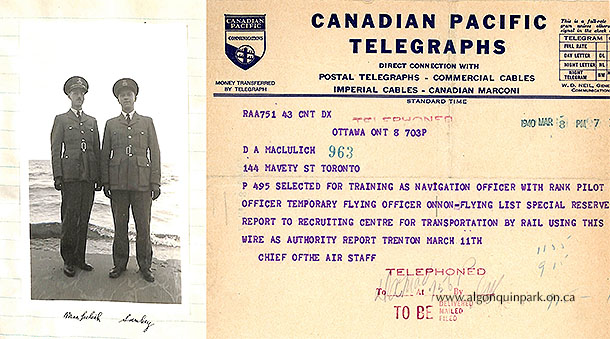

MacLulich was even with Professor Harkness studying the data of the trout research when he received a telegram requesting his arrival at the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) Trenton Station to undergo an Officer’s Navigation course as part of the war efforts for World War II. MacLulich served in the RCAF until his retirement at the age of 60, interrupting his time in the Park. However, he continued to publish and have correspondence with biology groups and professionals while he served, even publishing his trout survey in 1943.

Image: Left - MacLulich in RCAF uniform, 1941. APPAC 1977.9.97. Right - Telegram from RCAF to report for duty, March 8, 1940. Donated from the Collection of Dr. Duncan A. MacLulich by daughter M.A. Capstick.

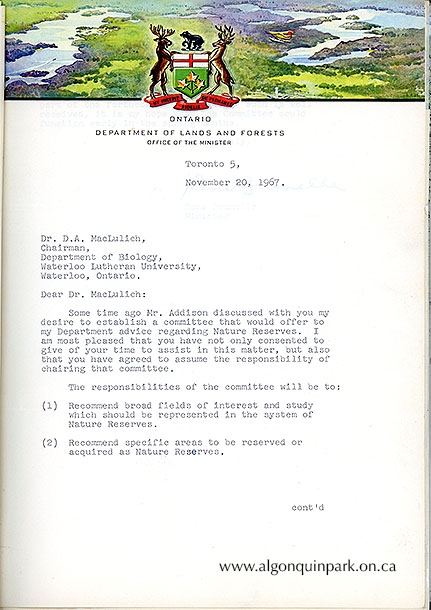

Upon his retirement in 1960, MacLulich re-entered academia to start his “third career” as a teacher and department chair at Wilfred Laurier University (WLU) (previously Waterloo Lutheran University). He returned once more to his roots, sitting on the board of an advisory committee created to recommend specific areas to the Government of Ontario that should be reserved or acquired as Nature Reserves, and to advise on broad fields of interest and study within those reserves.

The committee did slightly more than that, even creating a way to define areas of need, using the International Biological Program classification sheets to identify areas. In a press release MacLulich states that Nature Reserve Areas should be preserved “to be enjoyed by the present generation and generations to come [as] Once they are gone, they can never be restored”. These reserves would also be essential places for scientific investigation. When being interviewed about this system, MacLulich was adamant that all ecosystems of the region be preserved including those seen as ‘unique’ or special. As he states, “Unique means there’s only one of it and there’s hardly anything that’s that scarce”. MacLulich and the committee recommended and had the Coldspring Watershed designated as a nature reserve here within Algonquin Park, as well as other areas within Ontario.

Image: Memorandum from Ontario Department of Lands and Forests to MacLulich about the advisory committee for nature reserves. This letter is written by Minister Rene Brunelle, November 20, 1967. APPAC, 1977.9.57. Donated from the Collection of Dr. Duncan A. MacLulich by daughter M.A. Capstick

MacLulich’s early history with Algonquin Park was not forgotten in his new role. His personal history with the preservation of ecosystems had begun almost 30 years earlier on a camping trip with his father.

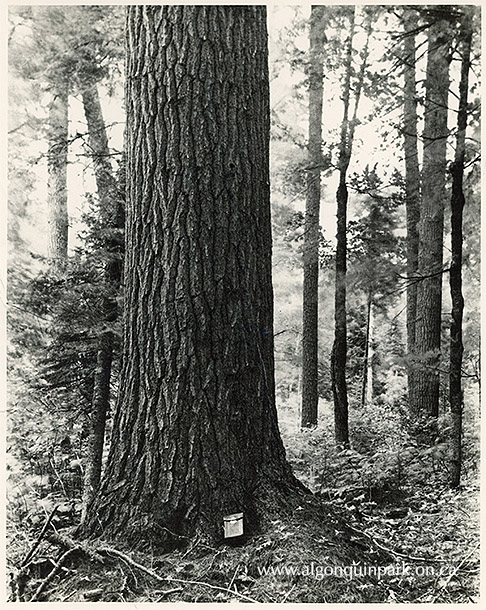

When MacLulich was a Ranger in 1938, he and his father, Donald MacLulich, had travelled up the Crow River (North of Lake Opeongo) in search of White Pine. MacLulich had heard that there were some good pine trees up there, and so they searched, finding the pristine forest of old growth pine. Upon returning, MacLulich tried to preserve this area as a “White Pine Monument” for fear that a lumber company would log it, cutting down the impressive trees. He reached out to Superintendent MacDougall and the Federation of Ontario Naturalists with no luck.

Image: Old White Pine from Big Crow Lake, 1938. APPAC, 1977.9.208. Donated from the Collection of Dr. Duncan A. MacLulich by daughter M.A. Capstick

Even on this advisory board in the 1960s, MacLulich never forgot about the White Pine at Big Crow. In the 1960s he obtained a research grant to investigate White Pine within the Park. So, with a student from WLU, MacLulich began to search Algonquin Park for White Pine, to create a reserve and to study them. They searched all over the Park, hearing of areas through word of mouth. They used MacLulich’s ‘science van’ (a Volkswagen bus that he converted to a moving lab), a canoe, and some idea of the areas they were looking for.

Image: MacLulich on Opeongo Road, 1967. APPAC, 1977.9.237.3. Donated from the Collection of Dr. Duncan A. MacLulich by daughter M.A. Capstick

Algonquin Park Superintendent Bill Hueston became very excited about their project and asked them to expand their search to inform the Park of other areas to be preserved. They received additional support from the Park and were flown in the Beaver aircraft to search for White Pine. During their search, they found a large area of pine at Big Crow, the area MacLulich and his father had visited in 1938. Unknown to MacLulich, Superintendent MacDougall had preserved a small section of trees. The area at Big Crow was perfect for MacLulich’s study, and their field work was finished in 1966, the report delivered in 1968. The area was expanded and became a nature reserve, which over the years has been visited by many canoeists who walk the same trail MacLulich blazed all those years before. MacLulich even created a movie about their work, “Searching for the White Pines”, an early form of science communication our current researchers still employ today to educate the public about their studies. Today, MacLulich’s data, journals, films, and other collections are housed in, and made accessible to historical and scientific researchers by the Park’s Archives.

MacLulich was a staunch defender of wild and natural places, and a lifelong learner and a lover of Algonquin Park. Many that come here spend decades coming back to Algonquin Park, and MacLulich recognized the importance of preserving these environments. He is one of many who have benefitted and supported the continued preservation of Algonquin Park. The old growth pine that were centuries old when MacLulich saw them in his twenties are still around today to be protected and researched.

Image: George McGee, friend of MacLulich, under White Pine at Big Crow in August of 1974. APPAC, 1977.9.237.15. Donated from the Collection of Dr. Duncan A. MacLulich by daughter M.A. Capstick

Learn More

Learn more about the Algonquin Provincial Park Archives & Collections

- Explore the online database of photographs, archival records, and artifacts.

- Contact the Collections Coordinator to schedule a research appointment or discuss a donation.

- Read more by purchasing historical publications in The Friends of Algonquin Park’s bookstore.

- Support the Archives with a financial donation via The Friends of Algonquin Park, a Canadian registered charity, to assist us in preserving Algonquin Park's cultural heritage for future generations.

July 22, 2025

The Little Donkey Engine That Could

Each July the Algonquin Logging Museum is brought to life during Loggers Day, a special event hosted by The Friends of Algonquin Park and the Algonquin Forestry Authority in cooperation with Ontario Parks. Through this day of demonstrations, interpreters tell the stories of the objects, machines, and buildings that depict the eras of logging along the museum’s trail.

Each July the Algonquin Logging Museum is brought to life during Loggers Day, a special event hosted by The Friends of Algonquin Park and the Algonquin Forestry Authority in cooperation with Ontario Parks. Through this day of demonstrations, interpreters tell the stories of the objects, machines, and buildings that depict the eras of logging along the museum’s trail.

One such piece of equipment is an oddly named machine, tucked away inside a log cabin.

This section of the trail begins the story of the technological revolution when machines replaced the man-powered, horse-powered, and water-powered ways of logging. But step inside the cabin, and you’ll see a machine that was not built to replace horses in logging companies, but to help them.

Image: Left: Log cabin at Station 16, Algonquin Logging Museum. Right: As your eyes adjust to the dim interior, a large machine towers over you – the donkey engine.

The donkey engine completed a task that a team of horses could not. Horses’ incredible strength was ideal for pulling heavy sleigh loads of logs downhill or on flat land, but they could not pull them up steep grades of hills. Usually, this limitation didn’t matter. Logs were being taken downhill to a river or lake where they would be piled high until the spring melt. But sometimes loggers needed to move logs over a height of land. The company may have established haul roads over that hill, or an improved water route for the river drive, that they needed to reach.

Image: A horse team pulls a sleigh of logs in winter near Brule Lake, c. 1935-1936. A man stands on top of the load, holding the reins. A large pile of logs and a jammer are visible in the background. APPAC, APM 3655, W. Coutts.

The development of the donkey engine solved this problem. Essentially the machine is a steam powered winch. After a horse team reached the bottom of the hill with their load of logs, the sleigh was unhooked from the horses and attached to the cable running from the donkey engine. The horses were removed so that if the cable broke, they would not be killed by the slipping and falling logs and sleigh. The donkey engine would winch the log sleigh up the hill, just like “the little engine that could”. Once at the top, the cable was removed, and the horses could be re-attached to the sleigh to continue the journey.

Image: Detail of the winch on the front of the donkey engine, Algonquin Logging Museum. The thick metal cable runs through an opening in the building towards the hill where it would be attached to a sleigh.

|

Make a charitable donation to assist us in protecting Algonquin Park's cultural heritage for future generations. |

The donkey engine was enclosed in small wooden building. Men worked almost 24 hours a day to keep the machine’s steam powered boiler fed and working. The building not only protected the men but also the machine from extremely cold and freezing temperatures during the winter’s work! A wood stove and various tools and objects would have been found in this building. The stove was also essentially for warming the donkey engine before it was fired up for the first time each season.

These machines were used in many different work forces, not just logging, and came in many shapes, sizes, and capabilities. The name “donkey engine” or “steam donkey” originates from sailing and cargo ships which had small secondary steam engines for loading and unloading cargo, raising large sails, and running pumps. In the logging industry, donkey engines were also useful for loading logs onto rails cars.

Image: Logs are being loaded onto a railcar using a steam-powered winch which is housed in the building to the left. Lake Opeongo, 1910. APPAC, APM 3298, R.J. Taylor.

Like many objects along the Algonquin Logging Museum trail, this machine has a unique origin story. This donkey engine was built by Marsh & Henthorn Ltd. of Belleville, Ontario in the late 1800s to early 1900s. The machine was one of two that worked side by side at Proulx Lake, Algonquin Park in the 1940s. Markings on the machine read “J.R.B.”, likely the initials of lumber and railway magnate, John Rudolphus Booth. The J.R. Booth Company had timber limits covering the land where this donkey engine was located. They likely had the machine marked as part of their property for the logging operation. Once the logs were pulled up the hill at Proulx Lake, they would continue by sleigh, south and downhill, to a log dump area on the ice and shore of Lake Opeongo.

The two donkey engines were rediscovered in 1990 by Ray Townsend who was accompanied on his journey by Ron Cahill: both staff members of the Algonquin Forestry Authority. While working for a lumber company in the 1970s, Townsend had heard stories about a donkey engine somewhere between Proulx and Opeongo Lakes. Using aerial photographs and contour maps, he scouted possible locations. After only one wrong educated guess, Townsend and Cahill came upon the two donkey engines, the wooden buildings that had once surrounded them since rotted to the ground.

Image: Ray Townsend stands with one of the two donkey engines re-discovered near Proulx Lake, 1990. Although the wooden buildings that once sheltered the machines were long gone, other artifacts remained from the operation, including a wood stove visible in the foreground of this image.

At this time, Algonquin Park’s new Algonquin Logging Museum was being developed and Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources staff expressed interest in exhibiting these pieces of machinery. The AFA aided the project by retrieving the winches from the original site. Using heavy machinery, they delivered them to McRae’s Lumber Co. who sandblasted and painted them. In 1998, work was completed on a clearing along the museum’s trail to interpret one of the two donkey engines. The other was kept in storage.

Image: Heavy machinery brings the donkey engine to its new home down the trail at the Algonquin Logging Museum, 1998. APPAC, 2020.18.2.119, J. Mihell.

Image: Staff working with chainsaws to construct the log cabin around the donkey engine, Algonquin Logging Museum, 1998. APPAC, 2020.18.2.120, J. Mihell.

The donkey engine is just one of the many artifacts along the Algonquin Logging Museum’s interpretive trail that illustrates the changes in logging practices and the lives of those who worked in the industry. Whether you attend a guided hike, take part in Loggers Day, or wander the trail on your next trip through Algonquin Park, these objects eagerly anticipate telling you their stories.

Do you know what to do if you find an artifact, big or small, while exploring Algonquin Park?

Do not disturb, move, or collect the object! Archaeologists learn about historic sites by knowing the exact location of an object, how deep in the soil it was found, and its relationship to other objects around it! When an artifact is disturbed, all scientific value of the artifact is lost.

Help us protect and study our sites by:

- Taking a picture of the object with something for scale.

- Recording the location as best you can – GPS coordinates are good if you also make a sketch of the site.

- Reporting your observations to the Algonquin Park Visitor Centre.

Learn More