Events Calendar

Current Weather

Algonquin Park/Michigan Moose Transfer 1985

Below is "Those Magnificent Moose and Their Flying Machines" originally written by Dan Strickland, Chief Park Naturalist of Algonquin Park, published on April 25, 1985, and now available in the Best of the Raven, Volume 1.

|

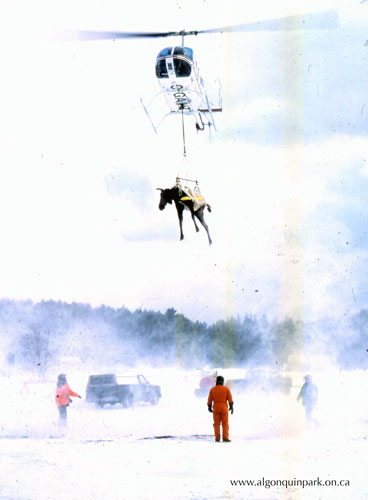

Tranquilized Moose being airlifted from Algonquin Park's backcountry to Mew Lake Campground for eventual shipment to Michigan. Image: Algonquin Park Archives MT-131 |

One of Algonquin Park's proudest traditions is helping to restore wildlife to other areas of North America. Over the years the Park has supplied beavers, martens, fishers, otters, and even deer to places that had lost their original populations of these species. By far the most spectacular assistance provided by the Park, however, was the successful transfer of Moose to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan in the 1980s. This article relates why the transfer was necessary and how it was carried out.

This is our first Raven for 1985, but we feel safe in betting that you have already read or heard about at least one Algonquin news item elsewhere this year. Back in January the press and all the Canadian and United States television networks carried prominent, coast-to-coast coverage of the spectacular transfer of Moose from the Park to the State of Michigan. Interest in the project was so high that for days on end two Park employees did nothing but answer enquiries and do interviews over the phone. And, even though it was the dead of winter, we actually had to erect barricades to keep the public from crowding in too close on the operation down at our Mew Lake base camp.

Without a doubt, the Moose transfer was the biggest and most important event involving Algonquin wildlife in years. Although the news is now several months old, we still think it worth while to devote a whole issue to the subject. Many readers may have caught only fleeting coverage earlier on, and, besides, we now have the opportunity to bring everybody up to date on how our Moose are doing in their new home.

|

Lifting a Moose by crane into a specially designed crate to be transported to Michigan. Image: Algonquin Park Archives MT-78 |

Before doing that, however, we need to explain why the project was undertaken in the first place. To understand that, you have to know how remarkably similar the release site of the transferred Moose, in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, is to Algonquin Park. Not only do the Upper Peninsula's forests look like ours, but also many details of their history closely parallel events that took place here. Both areas were originally populated by Moose, but that changed in the late 1800s and early years of this century when logging and severe forest fires destroyed many of the original forests. In both areas these changes favoured the temporary prosperity of White tailed Deer, a southern animal not really at home in the “north woods” but certainly capable of capitalizing on the second growth that followed the destruction of the first forests. The problem, as far as Moose were concerned, is that deer carry a parasitic brainworm which, although apparently harmless to deer, is fatal to Moose. When deer are numerous, any local Moose almost inevitably contract the parasite and die. Thus, although no one knew why at the time, the Moose populations of the Upper Peninsula and of the Park dwindled as deer numbers increased. By the early 1900's, Moose had disappeared altogether in the Upper Peninsula, and here in Algonquin they were certainly extremely scarce, if not altogether absent. Not very far north of Algonquin, however, was good Moose country that the deer had never invaded in any great numbers. This meant a source of Moose close at hand to repopulate the Park or augment any that were left if conditions ever changed. And, as every regular visitor to Algonquin knows, conditions have changed dramatically. The fires that created good deer habitat are a thing of the past, the numbers of deer have gone down, the risk of a Moose being infected with brainworm has correspondingly fallen, and now, in the last 10 years, Moose numbers have "exploded." We believe the Park population numbers about 4,000, and it may still be growing.

The same repossession by Moose almost certainly would have occurred in the Upper Peninsula as well, except that Lake Superior, lying between it and Moose country to the north, barred the way. It is true that some Moose cross over at Sault Ste. Marie at the east end of the Peninsula, but they are few in number. In any case, they have a long way to go through hostile, worm-infested deer country before they reach the suitable areas of the Upper Peninsula farther west.

Nevertheless, the fact that those newly suitable but mooseless areas existed led Michigan wildlife officials to reason that a Moose reintroduction would now work. All they had to do was "inoculate" the suitable areas with the nucleus of a new Moose population, and nature would do the rest.

That is the background for the "great Moose transfer of 1985." Rest assured, there was a tremendous amount of planning and consultation back and forth between Michigan and Ontario before all the details were worked out and work got started on January 21. The basic idea sounds simple. A small chase helicopter went out in search of Moose, preferably out on a frozen lake, came in close for a shot from a tranquilizing gun, and then hovered nearby to prevent the Moose from going back into the bush during the five minutes or so required for the drug to take effect and the Moose to go down.

|

A blind-folded Moose being prepared for shipment to Michigan. Image: Algonquin Park Archives MT-84 |

At that point a second larger helicopter came in with a crew of men, who fitted a special sling around the Moose so that the helicopter could lift it back to out base camp at Mew Lake. We shall never forget the scarcely believable sight of Moose after Moose being ferried in over miles of frozen lakes and forests. At first we would see just a tiny speck dangling below the distant helicopter until, as it came closer and closer, the "speck" resolved itself into a half a ton of blindfolded, ear-plugged Moose. Back then, however, there was little time to marvel. As soon as a moose was lowered to earth, another team of men (about half from Michigan and the rest from Ontario) went to work. Within 10 minutes of its arrival, the moose was weighed, measured, checked for pregnancy, given antibiotics, fitted with ear tags and radiocollar, relieved of a blood sample, tested for bruellosis and tuberculosis, and lifted by a crane into a special 1,000-pound crate to await shipment to Michigan. During all this time the animal's temperature was constantly monitored, and a veterinarian was ready to take remedial action should the temperature climb or fall from the normal range. Just before the crate was shut, and antidote was administered to reverse the effects of the tranquilizing drug and restore the Moose to full consciousness - which usually happened in two to five minutes.

Whatever the number of animals caught in a day - it varied from one to four - they were all driven on the same truck nonstop through the night on the 14 to 24-hour trip (depending on the weather) to the release site in Michigan.

|

Algonquin Park Moose ready for release in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Image: Algonquin Park Archives MT-94 |

All this sounds straight-forward enough, but the use of drugs is a tricky business at the best of times, and no operation of this magnitude had ever been attempted before. The project planners believed that 10 to 20 per cent of the animals would be lost due to drug-and-handling related stress and that it would take two years to transfer the desired 30 or so Moose. In fact, 29 animals (10 bulls, 19 cows-of which 18 at least were pregnant) were transferred in just two weeks, far surpassing the most optimistic predictions and making it unnecessary to stage a repeat program next winter. Another five animals, unfortunately were lost (three in the Park and two shortly after arriving in the Upper Peninsula), but four of the deaths were of Moose handled in the first two days of the project (when drug dosages were still being adjusted), and only one animal was lost after that.

The really important result is that the nucleus of a new Moose herd has been established in Michigan, and, if expectations are borne out, the population will reach 1,000 by the year 2000 - all thanks to the 29 Moose transferred this winter. As we go to press, all 29 are doing well and still live within 20 miles of the release site. Soon the cows will be having their calves, and the explosion will begin. The effect for Michigan of this handful of Moose will be enormous.

For Algonquin, also, the transfer was very important - not financially (the people of Michigan paid all the bills) or even ecologically (the temporary loss of our Moose is insignificant) - but rather in terms of our mission and tradition. The Park has a long history of helping less fortunate jurisdictions with wildlife restocking projects. Today, the descendants of Algonquin beaver, marten, fisher, otter, and even deer are all alive in various parts of North America. Being able to add the restored Moose population of Michigan to that list is a privilege of which we are very, very proud.

Updates

1987 - A similar transfer of Moose to Michigan was repeated in 1987. The two shipments established a core breeding population that by 1992 had grown to approximately 220 animals.

2010 - Read a lengthy update on the success the Michigan Moose transfer found in the Raven.

2013 - The population of Moose in the western portion of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan is now estimated to be 451.

2015 - The Michigan Department of Natural Resources is conducting a moose survey during the winter of 2015 that includes the western portion of the Upper Peninsula discussed in this article. Survey results are expected in late March or early April 2015.

Related Information

Reserve your developed or backcountry campsite for your next visit.

Share your passion for Algonquin Park by becoming a member or donor.

Special regulations for Algonquin's special fishery.